Boston Focus, 1.16.26

Boston schools: fewer kids or more families leaving?

Quite a few people asked me this past week what drove the decrease in Boston Public School (BPS) enrollment. Was it fewer children entering the system, or was it families leaving?

The answer is probably both.

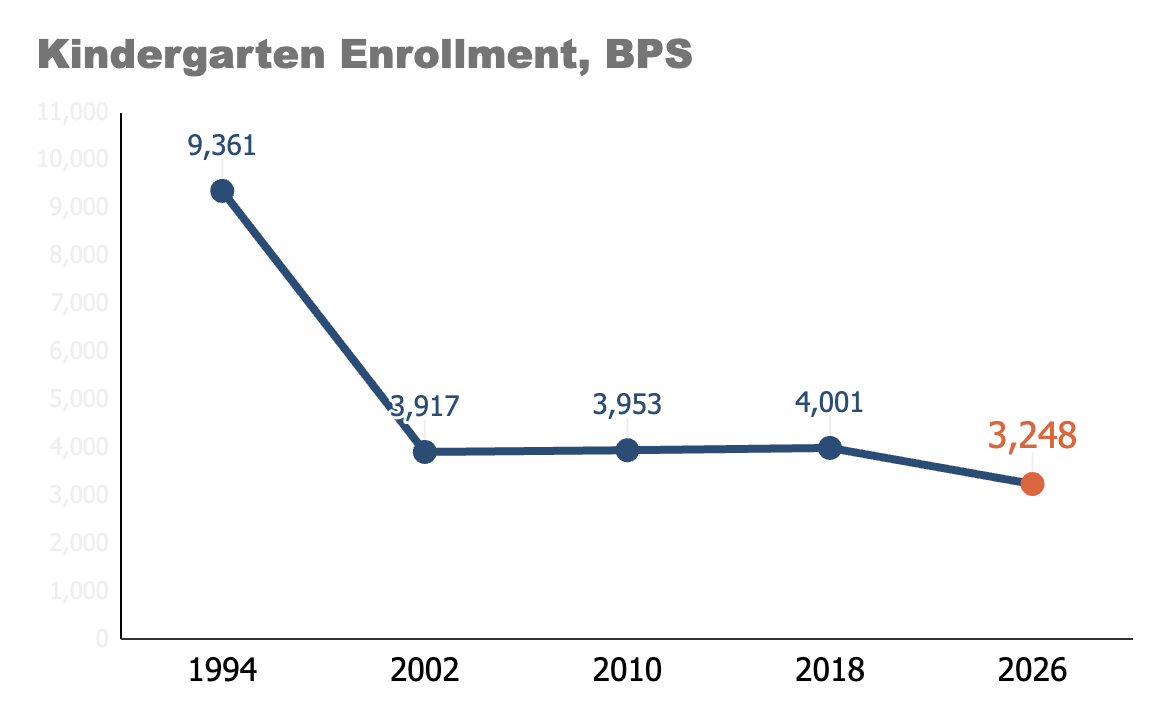

Coming out of the 1980s, the long-term economic boom in Boston created a city with an expensive housing market with more well-educated residents having fewer kids. Let’s start with kindergarten.

As the main entry grade, kindergarten serves as a bit of proxy of enrollment in general, and it is highly predictive of future enrollment (although often on a lag). Despite the very significant drop in 1990’s (down +5,400 kids in less than a decade!), it took more than a decade for cohorts of students to cycle through and observe the totality of the enrollment decrease it caused. That is why the superintendency of Carol Johnson (2007-2013) required school closures.

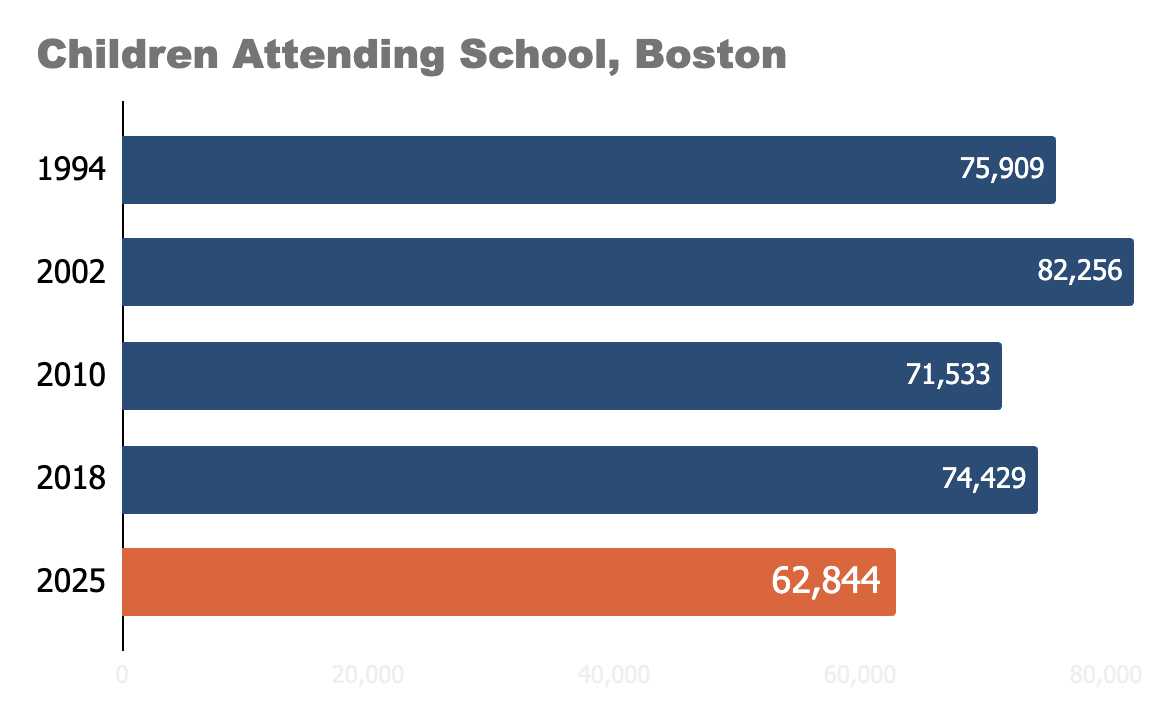

Kindergarten enrollment (and BPS enrollment) was stable for a long stretch, eventually declining with the pandemic. Some may blame the quality or length of remote learning, but the data does not imply this was a choice issue. The number of all school-aged kids in Boston fell by a ton, quickly.

Immigration played a critical role here. From 2000 to 2010, the foreign-born population surged in Boston, increasing 46%, but from 2010 to 2020 the rate of growth dropped to 16%. 2020 to 2030 data will be even lower, with the disruption of the pandemic and the relentless anti-immigration activities and rhetoric of the Trump administration. Nearly all Massachusetts communities with a significant immigrant population, including Boston, suffered large enrollment declines from last year.

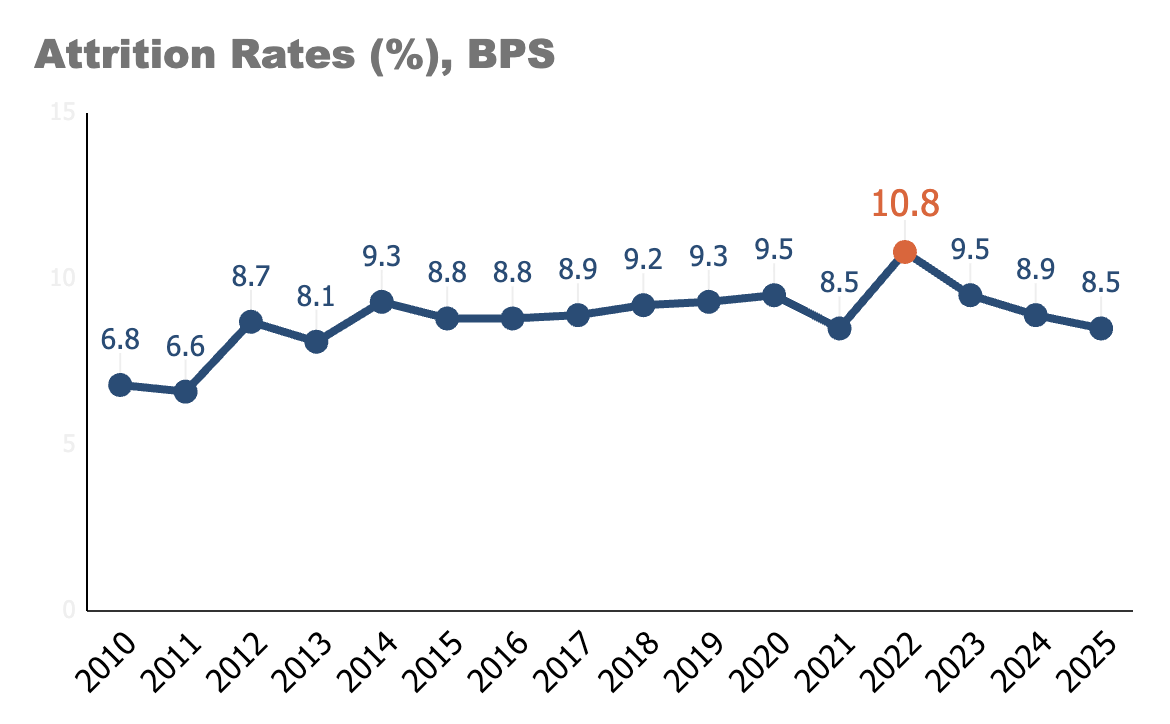

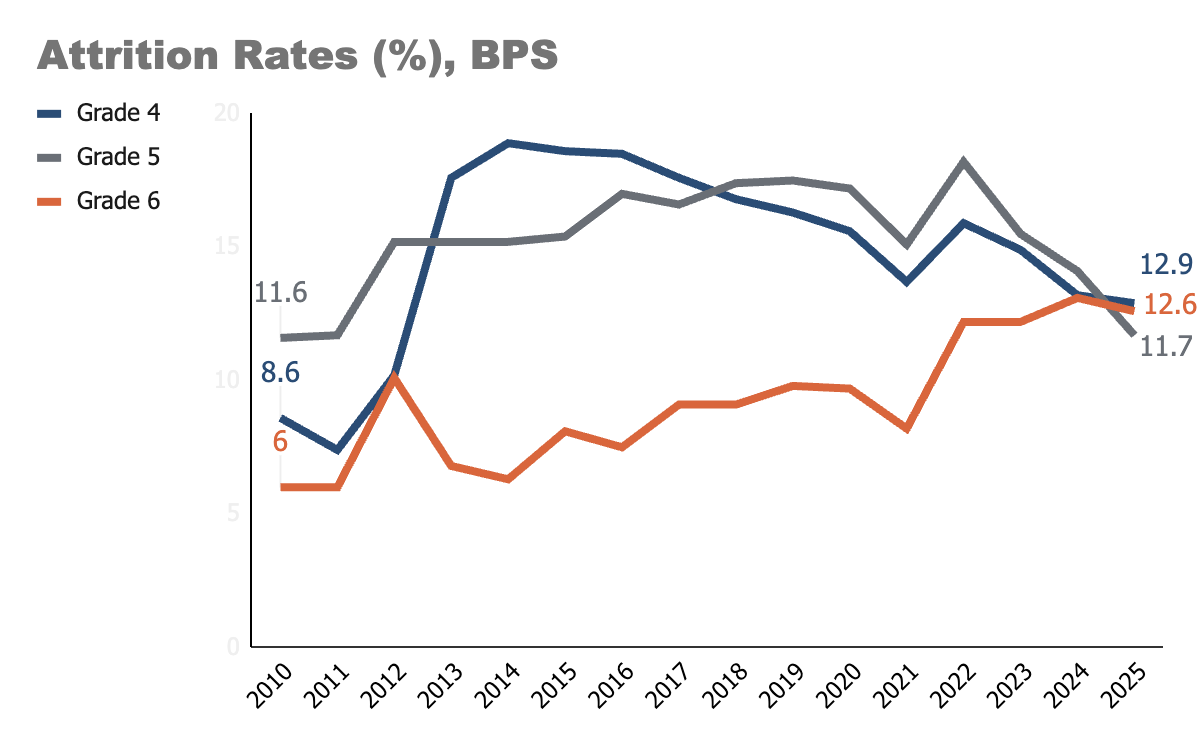

It is also true that during this time fewer families were choosing to keep their children in BPS. The best indicator of this is state-collected attrition data, the percentage of students that begin a school-year in a school system, but transfer out during or at the end of the school year.

One obvious factor here, again, is the pandemic. The highest attrition rates are during that time.

But when you zoom in, there are three grade levels that jump off the table and disproportionately drive the overall increase.

Why these grades?

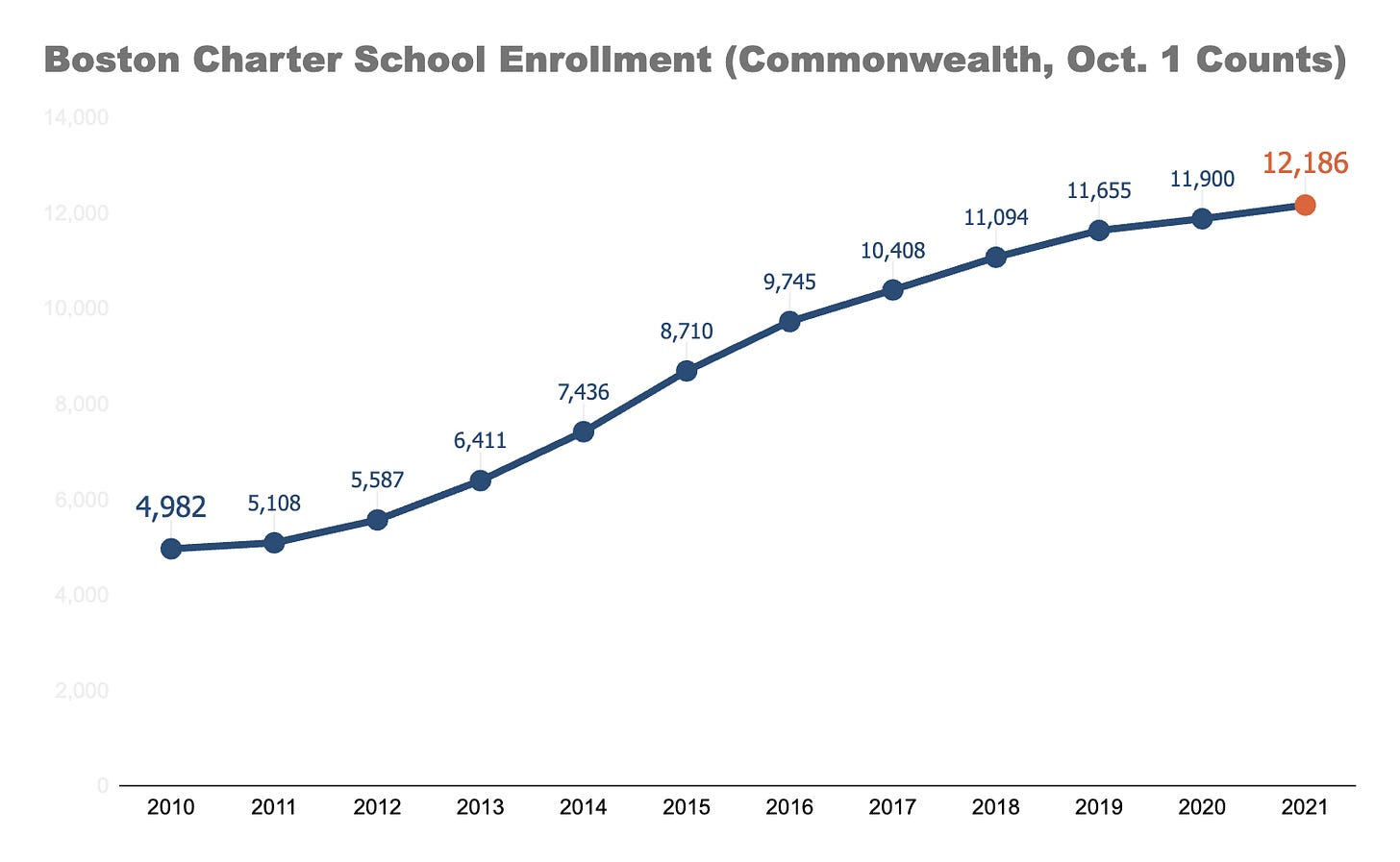

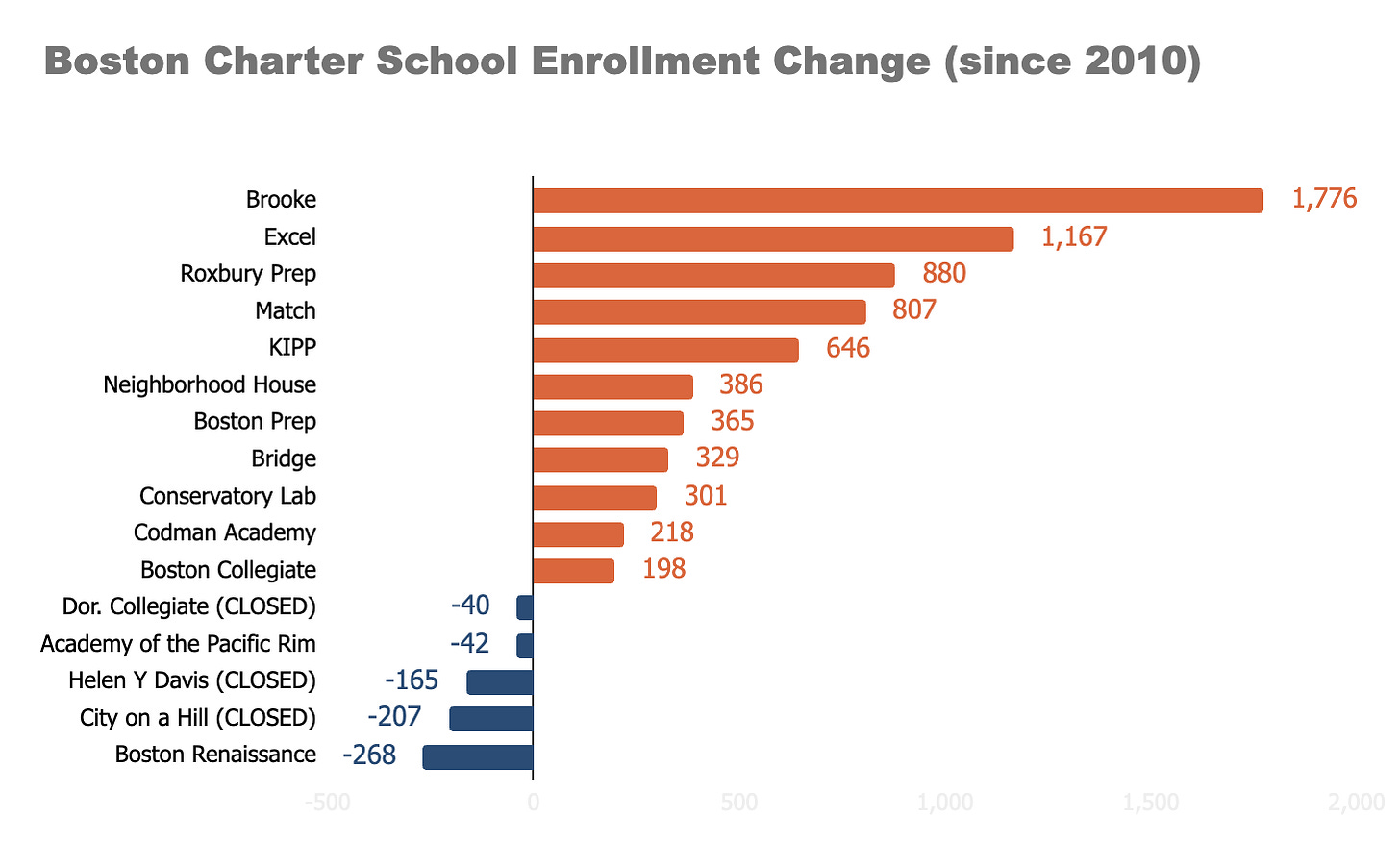

BPS enrollment decline was no doubt influenced by the growth of Boston charter schools, which were authorized to grow significantly following the 2010 Achievement Gap Act. In a little over a decade, Boston charter school enrollment increased by 7,000 students.

Every expanding charter school or network - but one - added middle school seats, with the most seats available in 5th and 6th grade. This clearly drove BPS attrition rates.

Since then, Boston charter school enrollment has leveled off, actually increasing by 72 students since last year. The past 30 years of data indicate that most Boston charter schools have lasting demand and will continue to fill their seats.

What about 6th grade attrition? The dramatic increase after 2021 can only be attributed to exam schools. As I have written in the Boston Globe, the overhauled exam school admission policy was complex and disadvantaged some students within BPS. A decline in applications to exam schools and anecdotal independent school data imply that a surge of families left BPS in 6th grade due to a lack of exam school access.

This fall, the Boston School Committee passed yet another iteration of the exam school admissions policy, which is far simpler and removes the “bonus point” system that dramatically skewed students’ admissions chances depending on what schools they attended. It will be interesting to see if this impacts attrition data collected this year.

Finally, what can we do about all this?

The frustrating answer is not much. Sound educational policy and schools can do a lot of good and drive parent demand. But all of that is pretty marginal compared to bigger forces of economics, demography, and culture.

What we can do is accept this as a reality, as Boston city leaders and BPS increasingly have. Poring over enrollment patterns, buildings, and budgets may seem technocratic or detached from students and educators. But ignoring it hurts classrooms. Fewer resources distributed inefficiently is what creates the current paradox of the BPS budget: how can many Boston schools can report more than $30,000 in per pupil expenses, yet lack the programs, time, interventions, and enrichment that Boston students deserve?

This year’s historically low kindergarten enrollment and at least three more years of decreased immigration tell me we have not hit the low water mark yet.

This is a big problem, in need of a set of big solutions.

Schools

A memo is circulating that BPS has a $53M budget deficit and hiring and spending freezes are in place.

While most of the attention on Madison Park’s potential move to Parcel 3 is political, little notice has been given to the actual plan for the school. The significant site size is not just due to vocational education needs. It assumes Madison Park can grow its enrollment by 1,200 students, in part by filling a new 7th and 8th grade. For this scenario to work, demand for Madison Park will have to match that of the city’s three exam schools.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the final cost of Madison Park is $1B. This may create an amazing building, but it leaves very little capital to make progress overhauling BPS facilities.

Boston International and Newcomers Academy (BiNCA) will move into the old Grover Cleveland building, vacated by this year’s round of school closures and consolidations.

Boston has set a goal to teach every kid how to ride a bike.

A bill that ensures evidence-based practices to teach every kid how to read may emerge soon in the Massachusetts Senate.

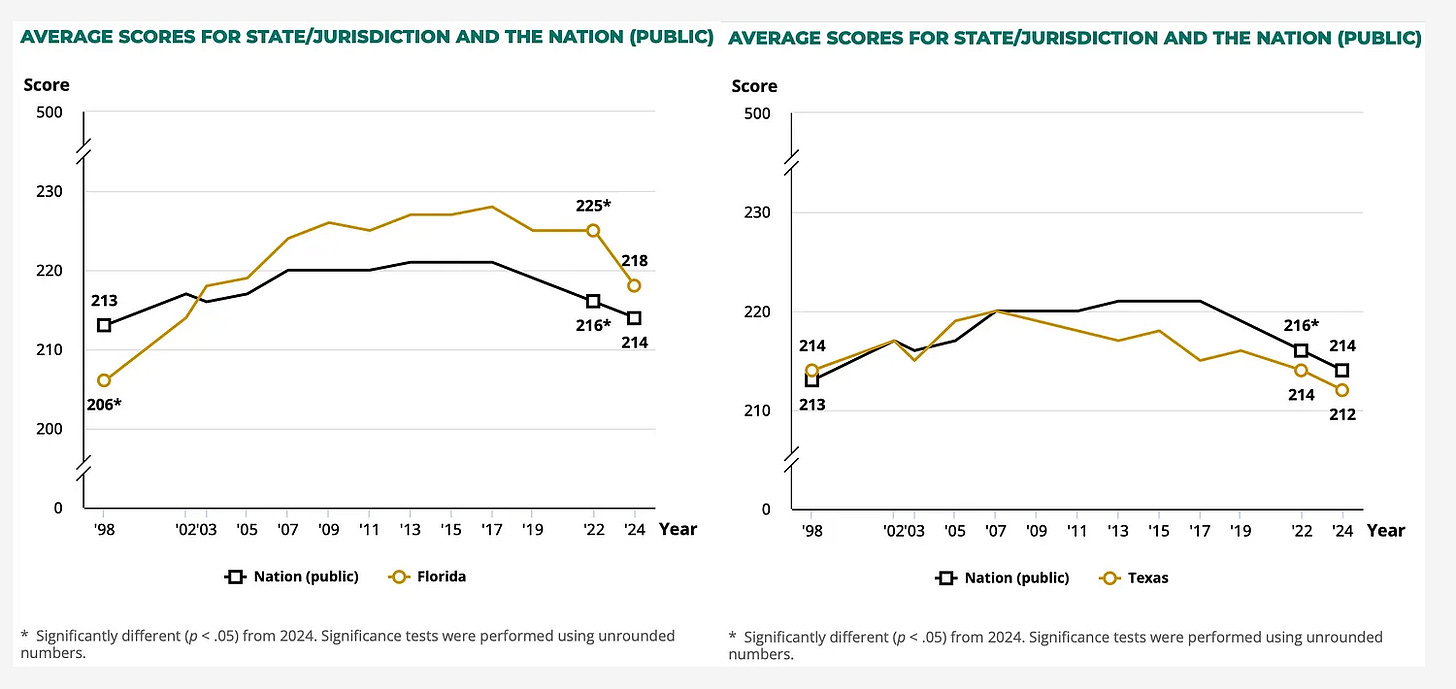

This legislation was inspired, in part, by the outsized literacy gains in Mississippi, which received coverage in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal this week.

The Mississippi data is real, but as Slow Boring points out, the narrative that Southern or “red” states have also figured literacy out is not.

Big study, simple summary: cons outweigh pros for AI in schools.

New York City is preparing the largest commitment to early childcare in American history: universal care starting at age 2.

Just in time for the midterms, the Supreme Court seems poised to weigh in on transgender athletes. Of all the school districts across the country, the Trump administration has chosen the home of the New England Patriots to investigate their transgender athlete policies.

All PR is good PR: Harvard’s foreign student enrollment has hit a record high.

Other Matters

The Massachusetts Senate rejected Boston’s proposal to temporarily increase commercial tax rates.

College sports is officially just like the pros: the athletes are paid and the games are fixed. The same gambling ring that ensnared former Celtic Terry Rozier systematically worked margins and plays in dozens of NCAA basketball games. Is anyone naive enough to think no one else is doing this? Former Governor - and now NCAA President - Charlie Baker is right. Prop bets are creating constant, widespread moral hazard and need to be illegal.

Live births in MA: 92k in 1990, 81k in 2000 and 72k in 2010. Immigrants helped mitigate the decline, especially in Boston and Gateway cities, but that is over. One aspect of the DESE data that jumped out is the rise of Asian enrollment in many Boston suburbs (Hopkinton, Lexington, Belmont and Acton among others). Is this growing Asian suburban community made up of some families that previously would have enrolled in BPS?