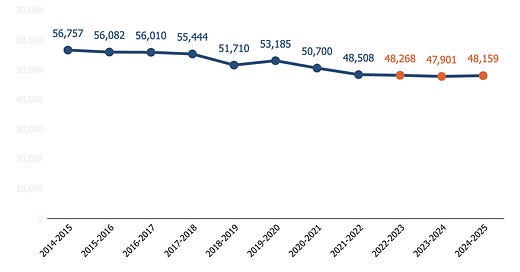

State data released last week indicates Boston Public School enrollment increased slightly this year, marking the third straight year without a significant decrease.

This comes as good news. Public comments by school officials reference a “stabilization,” perhaps dulling the financial and school closure pains created by this decline.

Over the past decade, enrollment decline has been diffuse, across school types and geography. The one exception is PreK, thanks to the continuous efforts of the Walsh and Wu Administrations to increase early education access (not even accounting non-BPS PreK seats added during this time).

The pandemic certainly accelerated enrollment decline, but these trends had begun years before, as documented by Boston Indicators, Boston Schools Fund, and others. Which is exactly why it is bit premature to write this off as a concern.

The fundamentals that drive enrollment decline have not changed. Housing in Boston is still expensive (and politically contentious). Birth rates have declined here and all around the country. There are fewer and fewer young Boston children (click on report, page 10). Alternatives - charters, METCO, independent schools - as a group have sustained demand (click on report, page 9).

Although precise data is not provided publicly, school officials cite the role of increased immigration in recently buoying enrollment. This is less of new development than it is return to a former normal. Starting in 1990s, Boston’s foreign-born population exploded, and student enrollment followed (well-documented by the BPDA here).

That was until the first Trump Administration. With its unfortunate sequel starting Monday and Massachusetts tightening its own shelter laws, banking on immigration seems tenuous.

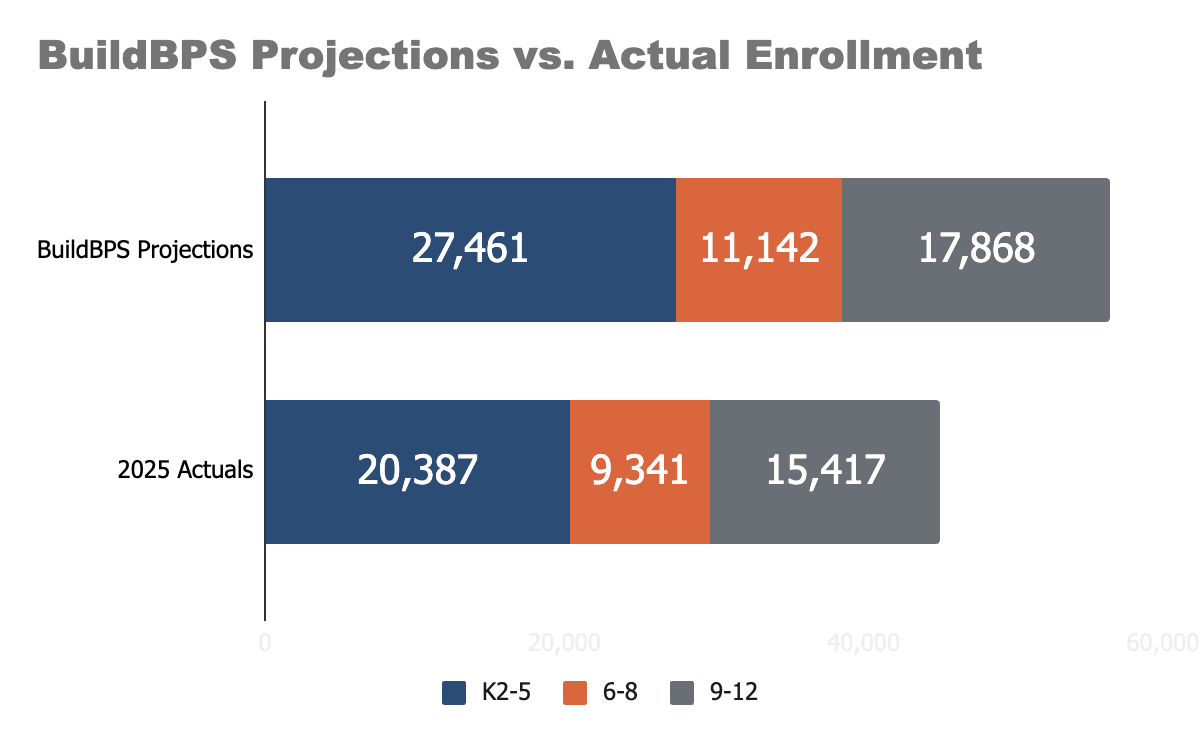

We needn’t rely on such speculation if the city had long-term, independent enrollment projection in hand. Currently, it does not. The last enrollment projection was published in the 2017 BuildBPS report; you can’t find this online anymore, but here is a copy.

The projection from seven years ago missed today’s actual enrollment by a factor of Fall River.

Around that time, in the infant version of this newsletter with about 60 people on a bcc, I wrote about Boston’s impending enrollment issues. Boston Schools Fund published multiple reports and webinars on the topic. I wrote a long piece in the Globe about it.

So, fair to ask: why do I care so much about this?

Firstly, there are real life consequences for getting this stuff wrong.

There isn’t a true cost for an underenrolled school building; it is an opportunity cost. School systems around the country that have lost enrollment like Boston could just continue to spend more and more money for fewer and fewer students relative to their administrative and capital footprints. It’s just really expensive, and begs the question what you could be spending the money on instead.

But the costs are not theoretical. Enrollment decline in Boston has wreaked havoc on individual school budgets, with school leaders and struggling to maintain programs without enough students (and the per-pupil funding) to sustain them. The short run solution has been lots of cuts (bad) and diverting tens of millions of dollars in “soft landings” to keep schools afloat (opportunity cost bad). That is money not being spent on academic programs, supplies, enrichment, and other things educators, families, and students value.

The federal stimulus staved off the worst of this, but as of last September 30, that money is gone. Rather than addressing these inefficiencies directly, the district chose to wave the problem away, eliminating public enrollment numbers and formulas from budgeting and planning last year.

In any case, this presents a false binary. Whether an underenrolled system funds per student or funds by program/school, resources are still going empty seats instead of full ones. Every classroom loses, often subtly. Kids and educators deserve more resources, especially if they could be made available.

More broadly, our world hitched our wagon to The Wealth of Nations around the time this country was being founded. One of the essential features of capitalism is that it requires and engenders constant expansion. The mark of emerging and then industrialized communities is population growth, driven by both improved living standards and the constant need for more supply to find more demand and vice versa.

The Baby Boom and the Dot.Com eras created the new Boston we had until recent history. In a new economy, Boston’s unique features attracted and aggregated talent, capital, and employment opportunities. Crime fell and people came to Boston to work, commuting from a distance or immigrating from afar to work at South Station, the Financial District, at mega-employers, etc. Cranes were everywhere.

Boston’s commercial riches reduced residents’ tax burden, creating general affordability with ample housing options. Inflation was low. Economic development paved the way for residential growth, and the school-aged population was steadily increasing.

That Boston is now in the past.

It is not certain what is next.

But it is difficult to imagine a future, flourishing city without more people living there and more children in its schools.

Schools

The expected pushback continues on the proposed slate of BPS building projects/closures. Families from the Mary Lyon and Dever have gone public, and the Emerald Necklace Conservancy has proposed an alternative for White Stadium that they claim would cost a fraction of the proposed plan.

A profile of Boston Day and Evening Academy.

School labor issues show no signs of subsiding. With continued concerns about pay and working conditions, the Massachusetts Teachers Association laid out their agenda for 2025. BPS teachers picketed outside of their schools yesterday.

“Inclusion” has been the accepted practice in education circles for sometime, and sits at the center of the most recent BPS-BTU agreement. What if inclusion doesn’t work, asks a noted special education researcher? Newton has learned that creating math classes with diverse achievement levels has been challenging.

The latter seems to be reflective of more general parental attitudes. A new poll from the EdTrust reveals significant Massachusetts parents’ concerns about their children’s math education. Toplines here.

Serious y-axis abuse by the New York Times here, but there is clearly a shift downward in child vaccination rates.

Most LA Unified schools have reopened.

Do colleges have too much administrative staff? Only if tuition-payers or donors won’t fit the bill, which does happen (case in point).

Signs of things to come for the next four years of federal education policy: votes taking sides on the culture wars and more public dollars for private religious schools.

Other Matters

Education was a theme in Governor Healey’s State of the Commonwealth speech last night. It is also tied, indirectly, to the speech’s star, the $8B proposed investment in the MBTA, which would require more funding from the millionaire's tax.

"We needn’t rely on such speculation if the city had long-term, independent enrollment projection in hand. Currently, it does not. The last enrollment projection was published in the 2017 BuildBPS report"

An enrollment projection seems like table stakes for any forward-looking planning on facilities.

Heard any word of plans to produce a new one?

Who's best suited to tackle this?