Boston Focus, 1.9.26

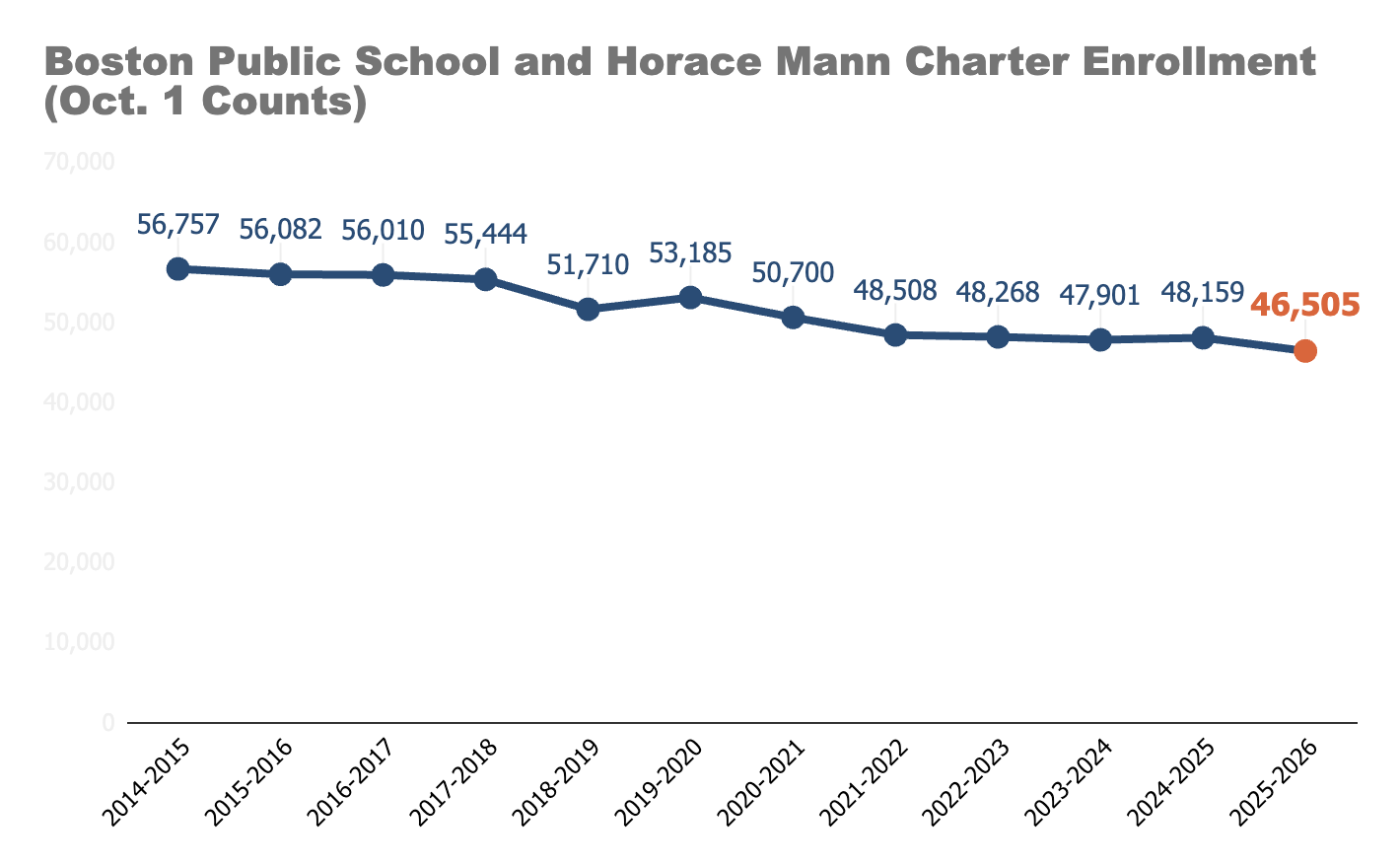

Boston Public Schools (BPS) enrollment declines for the 11th time in 12 years

Despite last year’s talk of “stabilization,” state data released last night shows that enrollment problems in Boston Public Schools (BPS) will not go away.

This was expected. The city began floating this possibility before school opened, and even previewed internal data this fall. What was unexpected was its scale. At -3.6%, it is the largest annual decrease, save the year following the start of the pandemic.

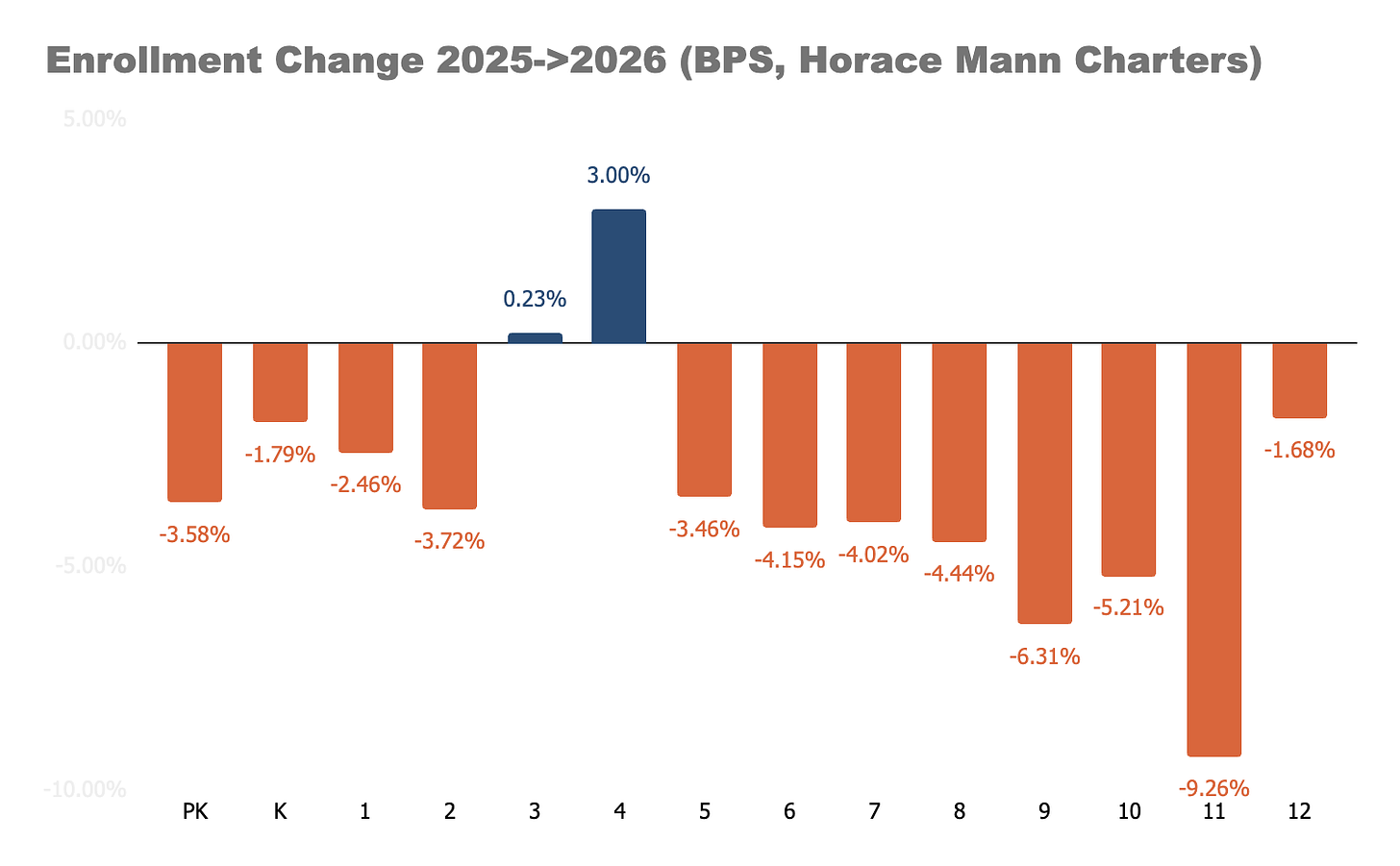

All but two grades posted enrollment declines from last year.

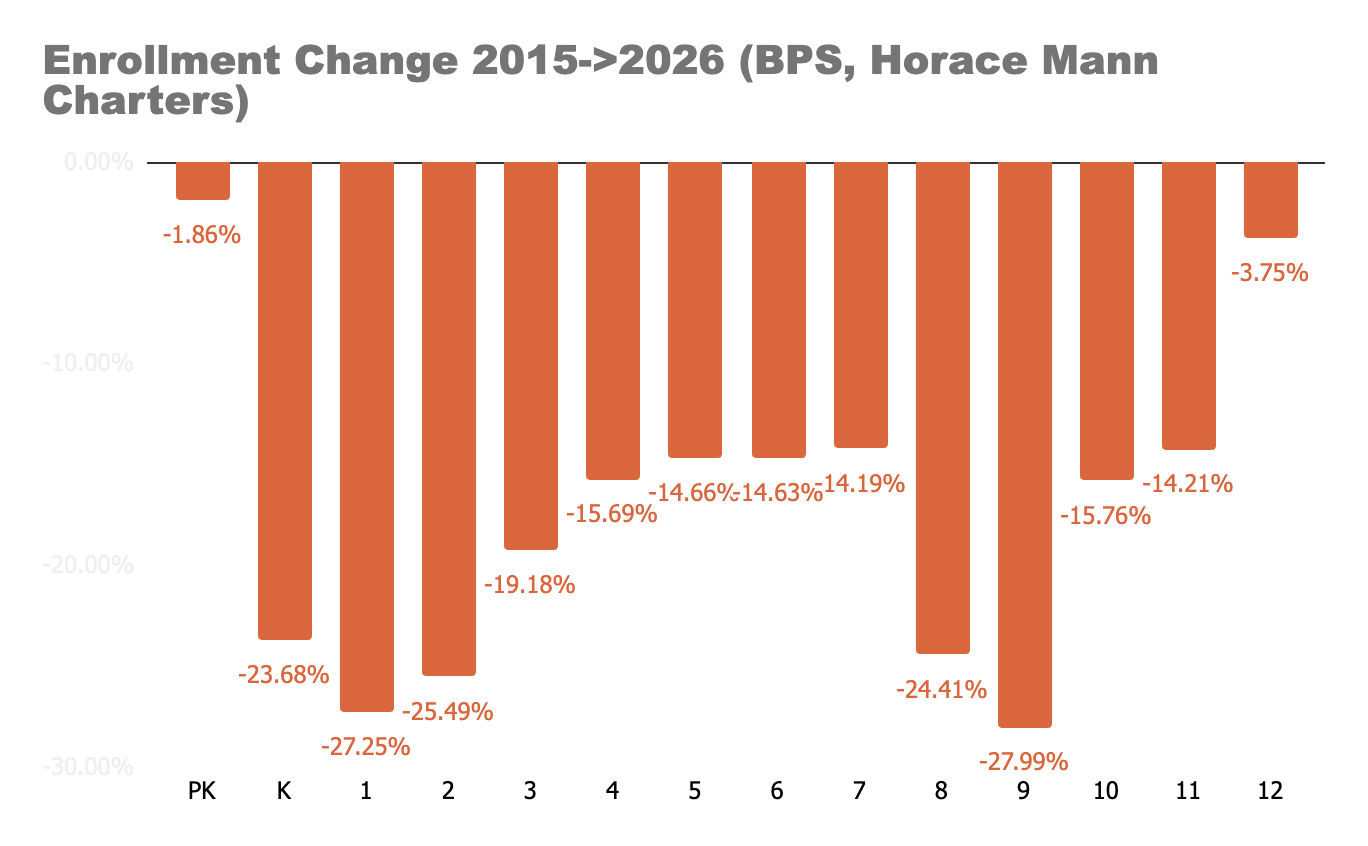

This most recent count brings the district’s total enrollment decline to -18% since 2015.

This applies to every grade level, although PreK data should be asterisked here because it does not capture seats in private schools/day care providers that are subsidized through Universal PreK (UPK).

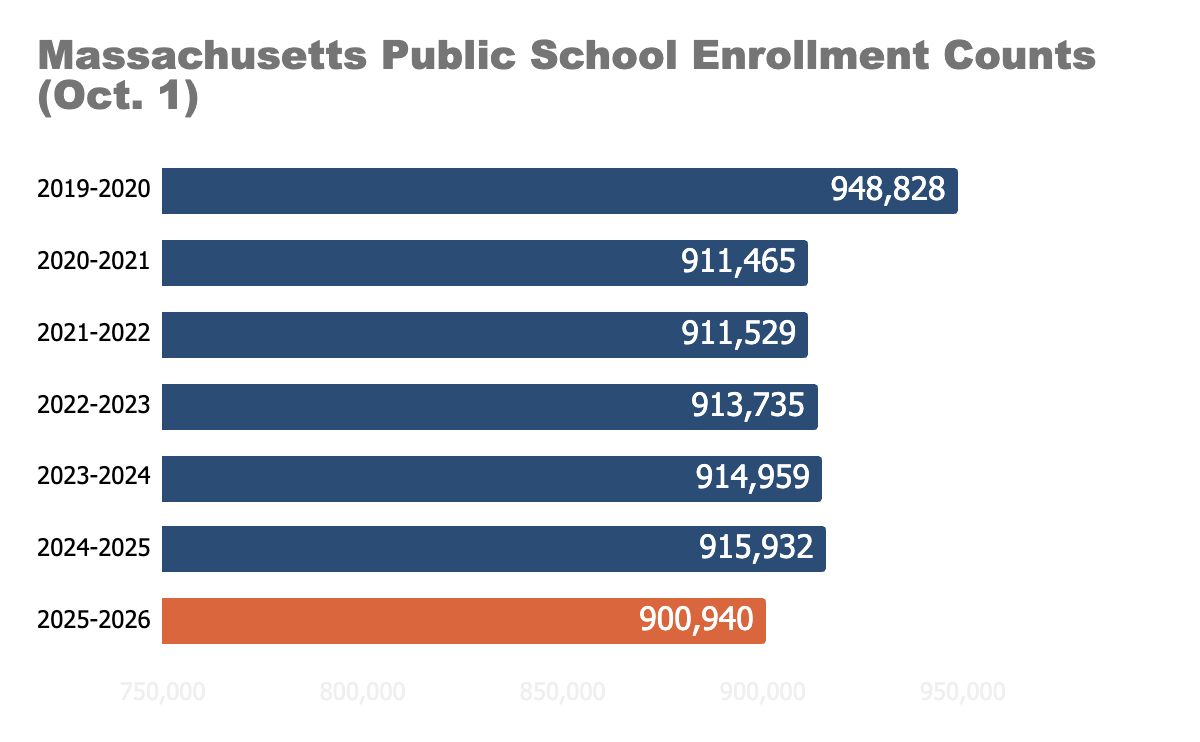

Massachusetts data indicates that this is reflective of a larger trend. Massachusetts public school enrollment decreased for the first time in five years; like Boston, the Massachusetts enrollment drop was its largest aside from 2021.

There are nearly 50,000 fewer children in Massachusetts public schools than a decade ago.

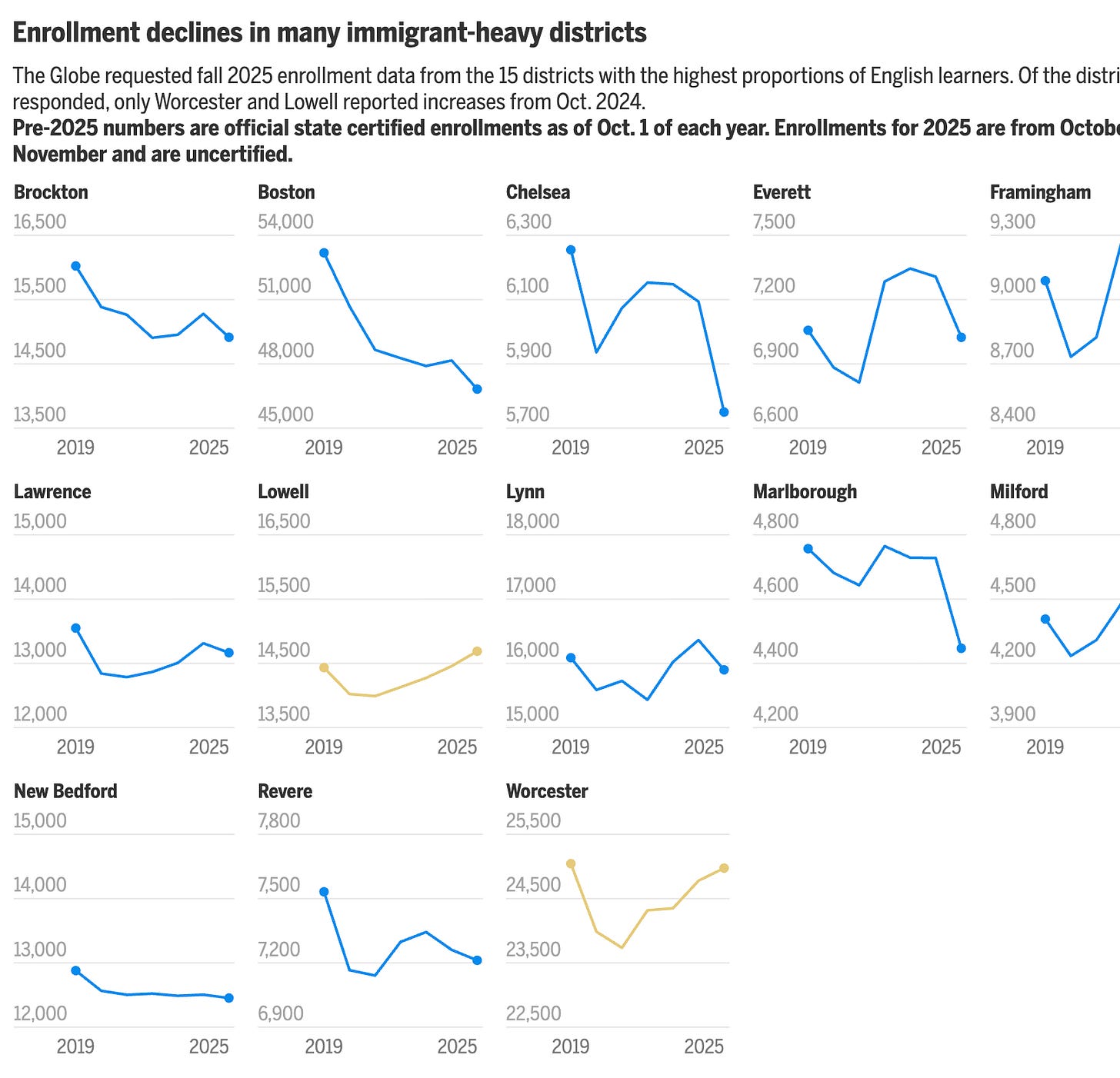

I have written a lot about the multiple, long-term factors that have pushed down the city’s and the Commonwealth’s child-aged population. But I think it safe to infer this most recent dip stems from changes in federal immigration policy.

Boston’s English learner population decreased by nearly a percent, the greatest annual recorded decline. Boston’s Latino student population decreased on a percentage basis (-0.4%) for the first time ever since this data has been collected and publicly reported in 1993. Lower 9th grade enrollment is another tell; it is common for most high school aged newcomers to be placed at the entry level for high school. Data from other Massachusetts school districts with larger immigrant populations appear to validate this.

Past is probably prologue here: BPS enrollment decline coincided with the first Trump presidency, and the first year of a second term implies history is set to repeat itself.

What is different this time is that the problem of enrollment has continued to compound. Now at -10,252, the recent loss of Boston students is now greater than the entire student population of the city of Quincy. Fewer newcomers and the year-over-year drops in kindergarten and 9th grade - which are highly predictive of future enrollment - portend more years of fewer students.

As this profile of Mayor Wu demonstrated, there are no easy policy answers for the many factors that have made Boston a city unfriendly for families.

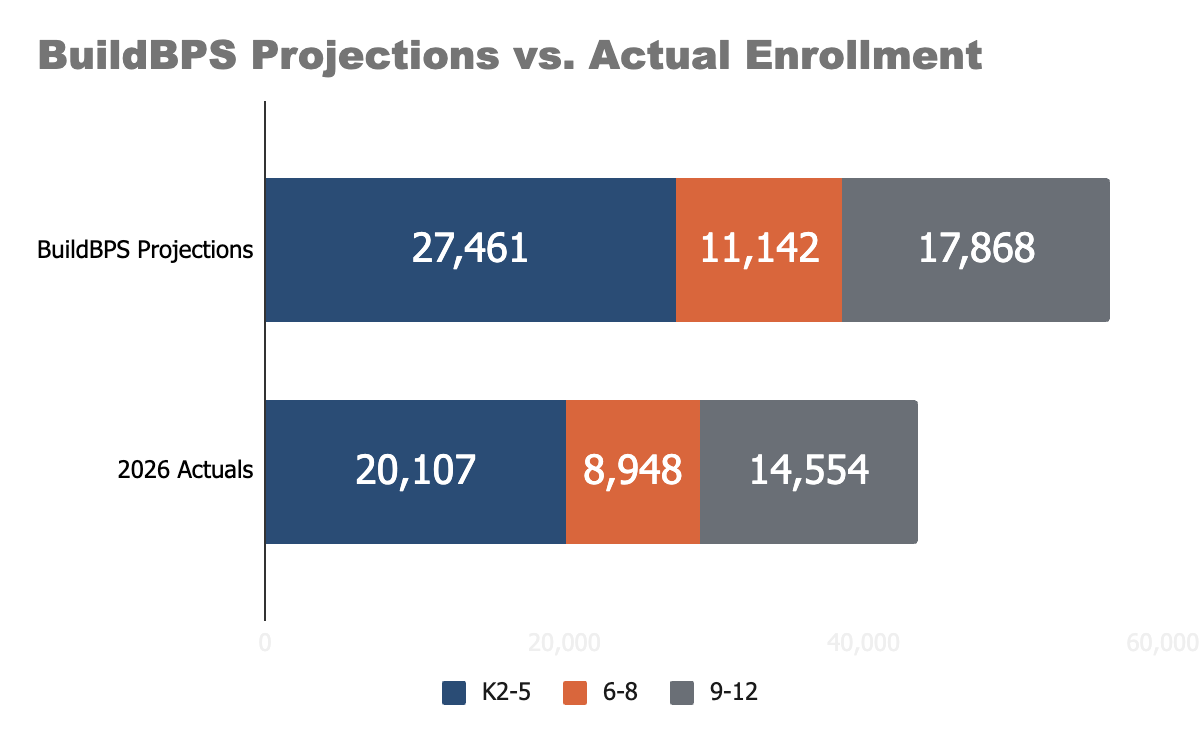

The first step is getting your hands around the problem. The city has not commissioned an independent, expert enrollment analysis since 2015. That analysis, which created the baseline for “BuildBPS” facility initiative during the Walsh Administration, is now painfully incorrect and obsolete.

The big things that drive the district’s budget and initiatives - staffing and staffing ratios, inclusion, buses, a master facilities plan, etc. - all rely on realistic enrollment projections and managing resources to meet children and educators where they are and where they will be. This mismatch of resources becomes only more painful in a scenario where BPS and other city departments have been asked to plan for budget cuts next year.

It is not enough to acknowledge all of this this as a problem. It requires real numbers and real plans.

Schools

The new year brought some education news: Mayor Wu indicated an openness to reforming student assignment and busing in her inaugural address and Boston has two new School Committee members.

Boston School Committee did meet briefly on Wednesday. Meeting materials here. Rachel Skerrit was elected Vice Chair.

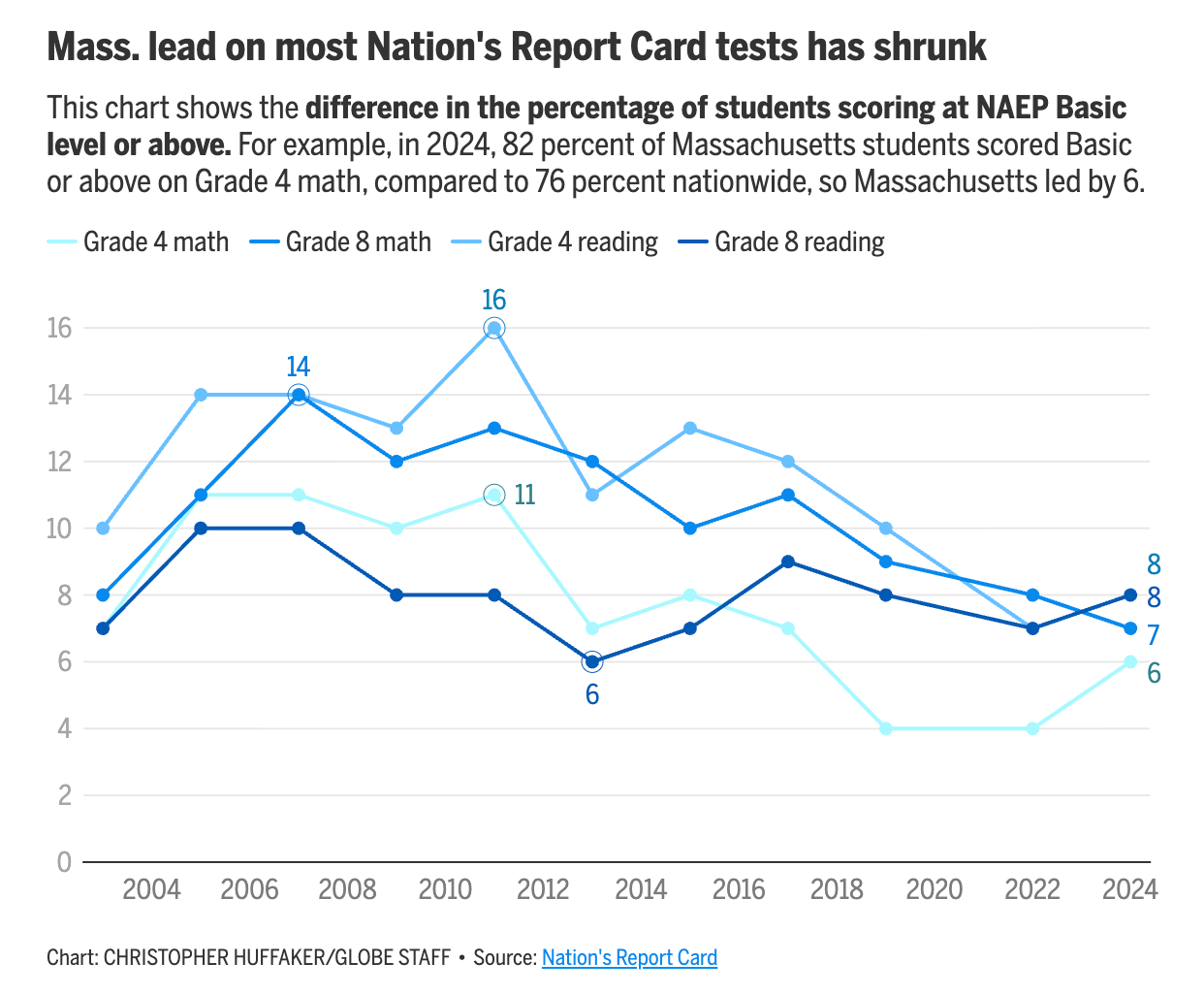

As a reminder, Massachusetts’ perch atop public education is not as high as it once was.

But perhaps not in vocational education: Massachusetts technical high schools received a glowing Wall Street Journal treatment.

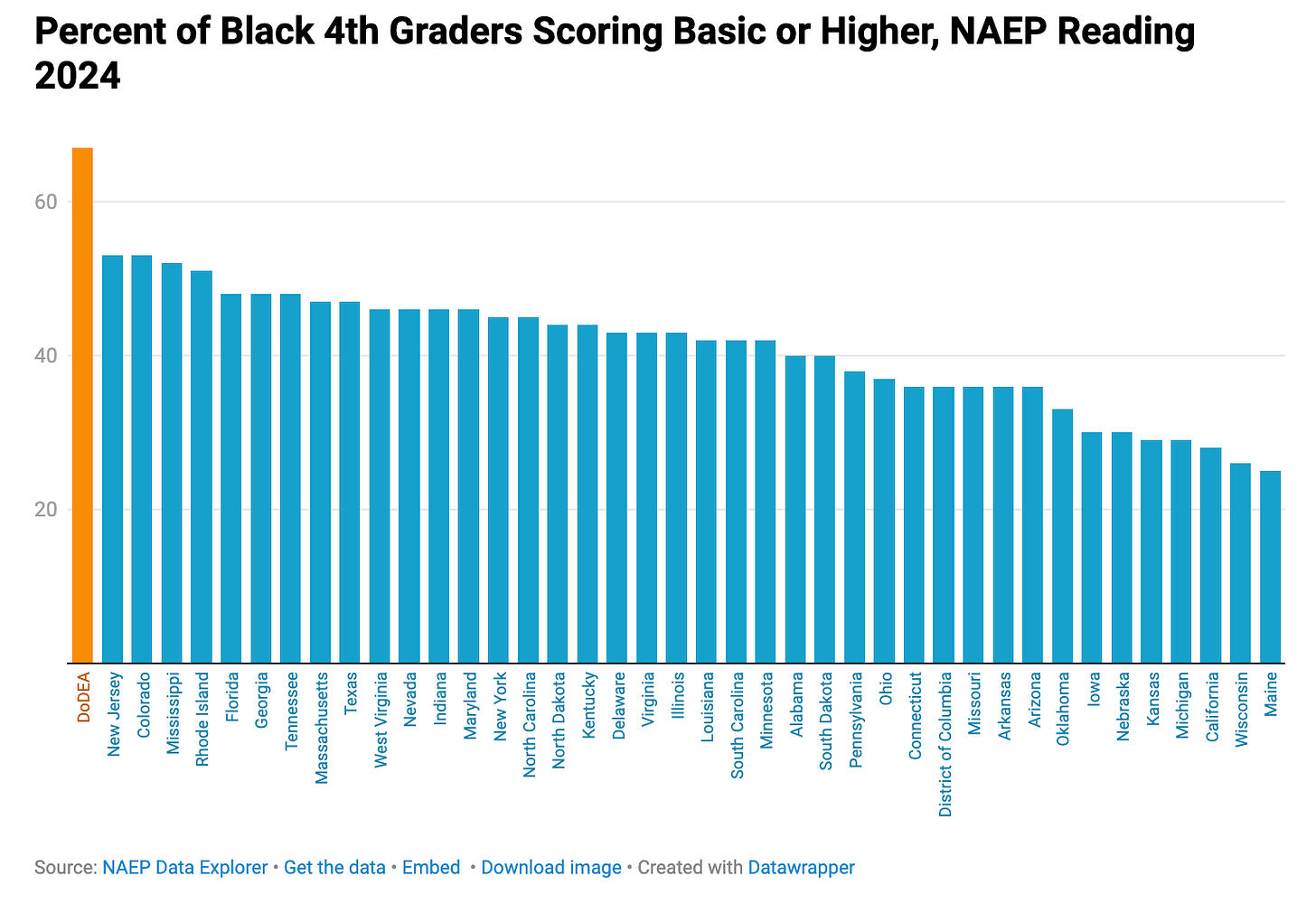

Tim Daly goes deep on some of the most effective public schools in America (despite the fact that many of them are not in America).

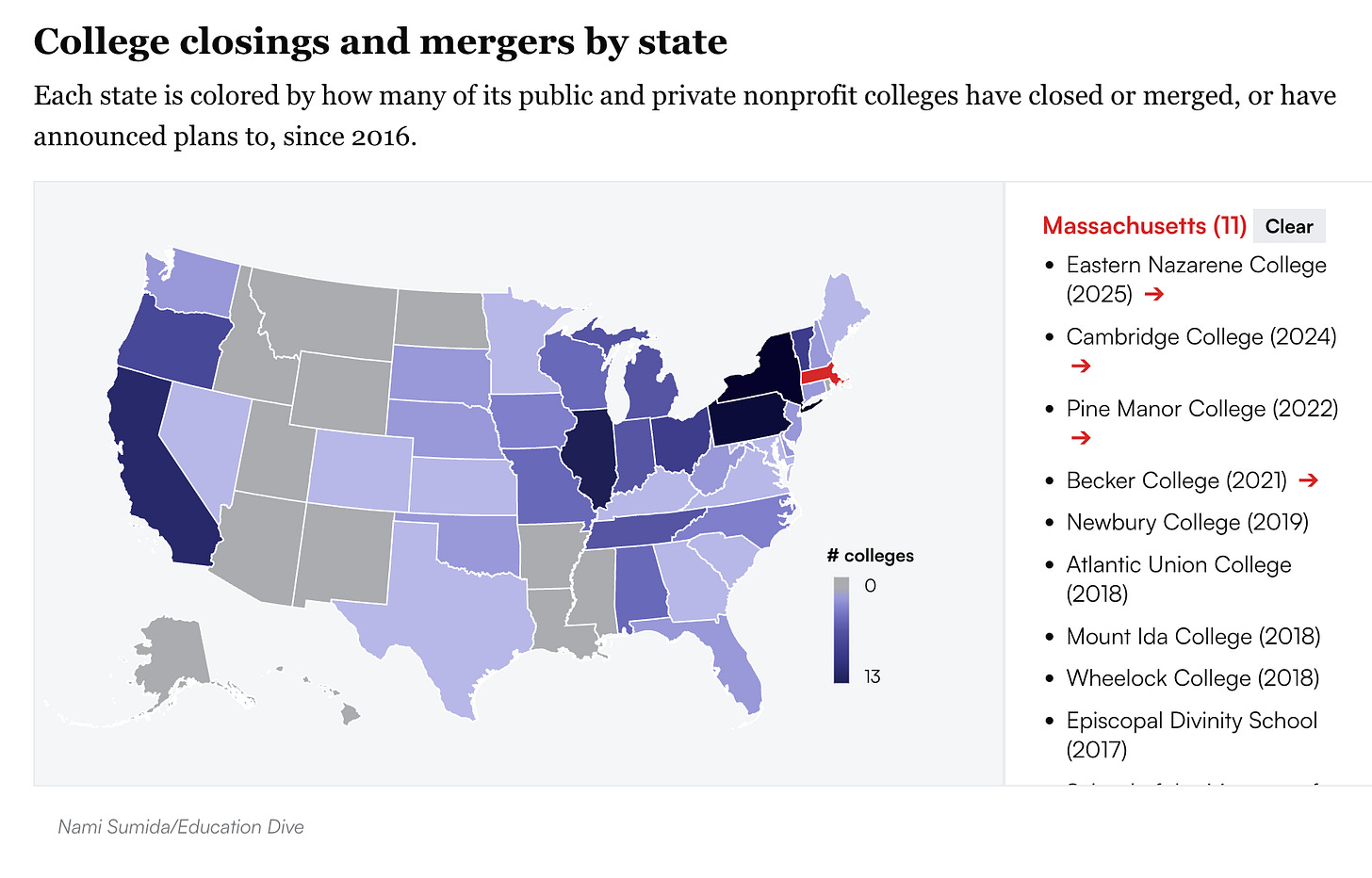

Massachusetts ranked third for college closures/mergers over the past decade.

These interviews with local college presidents present a bit of a missed opportunity to really dig into the market forces bearing down on colleges right now. It’s not just small liberal arts schools - the new endowment tax will create trade-offs at even the wealthiest higher education institutions.

Other Matters

What U-Haul data says about where Massachusetts may be going.

This story on increasing health care costs and its impact on local budgets begs two reminders:

This year Massachusetts will spend ~$22B on health care, by far the largest item in the state’s budget.

Past research indicates that additional funds for public schools in Massachusetts were likely to be spent on health care costs for educators.

Is there data that indicates to what degree the decline is due to denominator (potential BPS families / leaving Boston) vs the numerator (families who still live in Boston opting their kids out of BPS)? Is there a metric that controls for the denominator and tracks the percentage of Boston school aged kids who enroll in BPS over time?