Boston School Committee met last night, releasing its first round of comprehensive budget documents for FY26. Find them all here.

As previewed in last week’s meeting, the district’s priorities have been consistent, “building on” past investments. An example:

There will be many more hearings before the School Committee votes on the budget in March, and even more hearings at City Council before Councilors must vote on the budget before June 30. But, if past budget seasons are a guide, what is presented last night will be basically what is enacted for next year.

Why?

The fundamentals of the budget - revenue, staffing, enrollment, etc. - are now set. Sure, there are changes and noise outside of these domains - transportation is up 10% again, for example - but the big drivers of the budget define what BPS can and can not do with the money it has.

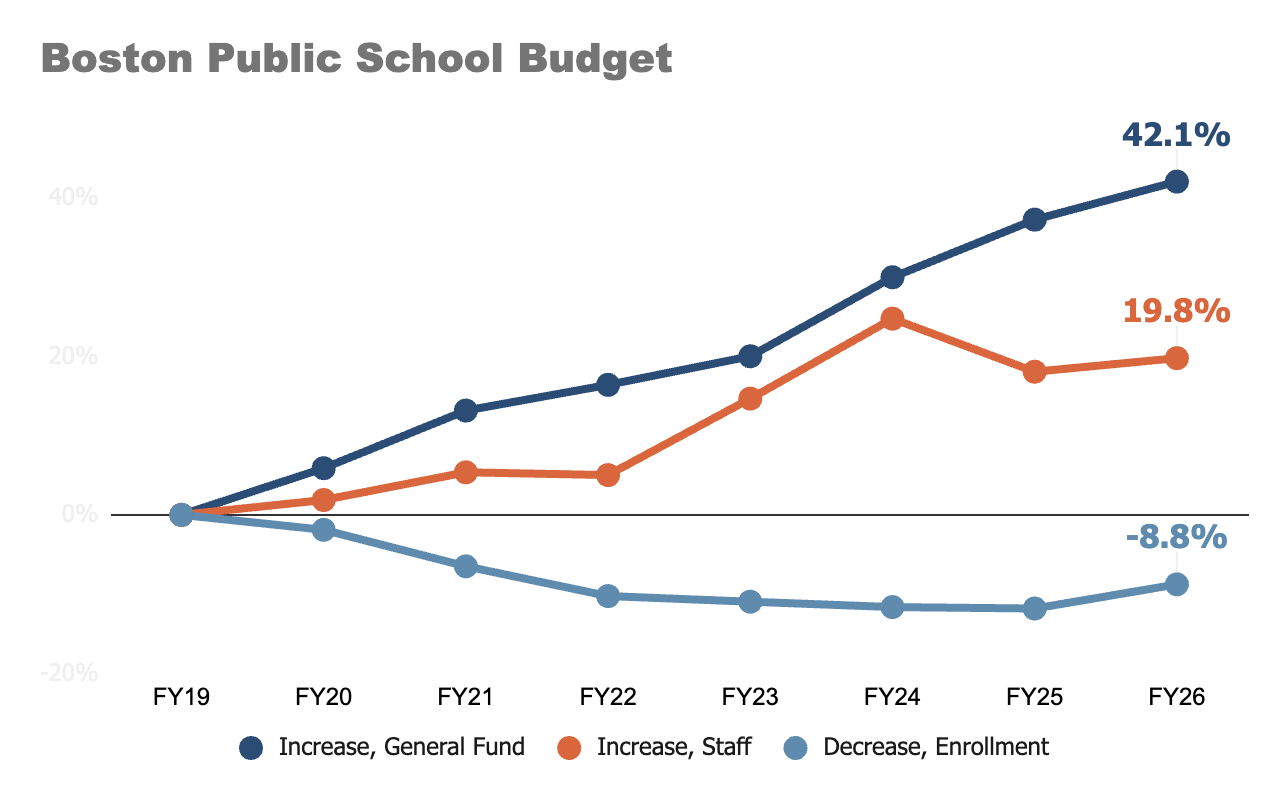

Including federal and state funding, the Boston Public Schools (BPS) budget is proposed to increase by 3.7% next year.

This follows a fiscal year with a decrease in the overall BPS budget for the first time since the Great Recession, due to the end of federal pandemic stimulus spending (“ESSER”).

This also helps to explain the shape of staffing at BPS. After a slight dip due to the elimination of temporary roles funded by ESSER, staffing increased again this year, now up about 20% in the past decade.

This is possible because Boston is footing the bill. With state and federal dollars holding mostly steady, more dollars had to come from the city’s general fund.

There has been a 62% increase in the past decade.

This has accelerated trends economists have noted in school districts and states across the country: increased spending, increased staffing, and fewer students.

Boston’s per pupil spending has dramatically increased (now the highest of any major city in America), but that comes at a cost. Nearly no BPS school can afford their programming with their current enrollment (see page 2) and therefore need “soft landings,” additional funding to carry their empty seats. (Explained more in detail here.)

Factoring in additional funds for “quality” and enrollment transitions, that figure actually increased slightly from last year.

In total, since 2019, one-quarter of a billion dollars has been allocated to Boston schools that were underenrolled.

Even with big budgets, big expenses like empty seats leave little room for other things.

Schools

White Stadium moves closer to demo.

The city will ask the state to help pay for the renovation of Madison Park; without assured funding, construction initially planned to start of this year now seems unlikely.

A new coalition of superintendents, school committees, and teacher unions are advocating for a change in the state funding formula for education.

A Southbridge teacher won the Milken Educator Award.

Massachusetts must reform how it serves students with special needs, according to a federal review.

The latest Education Recovery Report Card shows American schools have a long way to go. Summary here. Massachusetts finds itself in the middle of the pack.

Even though their education was not interrupted by the pandemic, curiously, American adults are also posting literacy and numeracy declines.

What does effective implementation of “science of the reading” look like? Read this account from a teacher at the JFK in Jamaica Plain.

Does higher education need a brand makeover? MA leaders are spreading the word about opportunities for free enrollment and financial aid.

No one wants to create a “Trump” section, but there was a lot more noise around education this week. Some of it was a continuation of existing issues: what deportations may mean for early child care, what immigration enforcement can actually look like in a school, etc. Or, coverage defaulted into the permanent campaign mode (resistance, fear).

Until recently, many people probably weren’t aware of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), an entity created during the George W. Bush administration to support PK-12 research and implementation of research-based practices. Now IES has entered DOGE’s orbit. (I realize that reads like a line from Star Trek.) The ~$1B in IES contracts that help to codify everything from literacy to special education practices is now possibly being cut.

Given the political backlash this may cause, many wonder how realistic cuts like this are. In her confirmation hearing yesterday, Secretary of Education nominee Linda McMahon stated clearly that federal funding for schools (Title I, IDEA, etc.) would not be decreased. Although, it is not entirely clear what her input would be if her department ceases to exist.

If you don’t think citizens will cut their own government aid to spite their self-interest, you are not familiar with the fate of America’s public swimming pools.

Other Matters

With City Council approving another attempt to shift Boston’s tax share away from residents to businesses, a new report presents a picture of Downtown that is not going back to a pre-pandemic “normal.”

I think the broader point here is that no matter how good/science-y an approach in education, the actual implementation and delivery is what matters. You see that time and again with various interventions and initiatives - "works" in one place, but then not another.

Not quite YIMBY, but the cities that have navigated this acknowledge the disruption and trauma caused by closing a school. And they provide recompense - giving affected families their first choice for a new school, timing decisions so affected families and educators immediately have access to a new facility, etc. But you can only this if you have a real master facilities plan with real, budgeted projected with timelines.