Boston Focus, 4.18.25

Boston school bus drivers, control or invest?, and why many Boston elections are already special

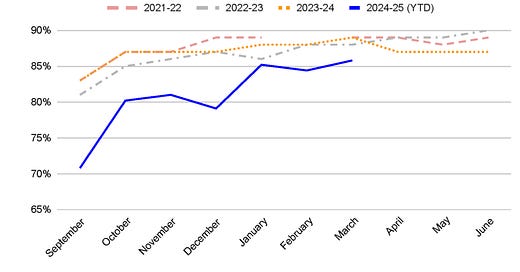

On Wednesday, Boston released a long report on the elusive goals of better on-time performance and reducing costs for its school buses.

The first big headline was a 94% morning on-time rate last month, the highest rate recorded in many years. Good news, but only half of the story: afternoon on-time rates are the lowest recorded in many years.

The district also announced pausing bus service for students who do not routinely ride the bus. It is the first major transportation policy change in some time and, from an efficiency standpoint, this makes sense. With data from the system’s new bus app, the district projects ~1,000 fewer students will be transported.

But will this actually save money or time?

The savings estimate provided is $3M-$5M (page 28), which represents only about 2% of the total cost of buses (~$186M in FY26). No calculation is provided, but it must be less gas or charging because there are certainly not fewer buses. As I have previously written, the number of buses has not decreased as Boston’s student population has. That, of course, is tied directly to bus drivers and their job protections, just recently extended with a new contract.

Traffic, requirements for non-BPS schools, and long bus runs all are cited as structural issues that contribute to challenges in the system. Any incremental gains by slightly reducing ridership could be outstripped by anything from bad weather to other inefficiencies, such as the increase in door-to-door transportation.

Buses are vessels, not just of children, but of policy decisions. Reforms and policies are well-intentioned but offer diminishing returns in trying to improve bus performance. At a certain point, one must accept Boston’s buses and how they perform as a reflection of the policy decisions we have made about student assignment and which students get which services.

You only will get different buses when you have different drivers.

Schools

Boston School Committee met on Wednesday. Full materials here. The big item was details of the now-approved Boston Teachers Union contract, including the price tag: an additional $180M over three years.

Massachusetts will soon have a new Commissioner of Education as the three finalists sat for their public interviews yesterday. Summary of the candidates here, and all 5+ hours of the interviews here.

What will this new Commissioner inherit? Continued calls for a literacy bill. A potential impasse on vocational education school admissions. Concerns regarding teacher turnover. Federal funding threats and an ongoing lawsuit to recover federal stimulus funds. Advocacy to limit cell phone use in schools.

The state education data hub had another release this week, including some positive data for early childhood education.

What are the standards for teachers - not students - using AI?

Tim Daly sounds the alarm bell for cities with declining student enrollment.

In a different time, what happened at FSU yesterday would have been the leading higher education story, even leading national story.

But the public escalation of the war between Harvard and the Trump Administration keeps getting clicks. There is a real question around endgame here. Regardless of Harvard or any other university’s refusal to capitulate or the Trump Administration’s reprisals, one underlying fact will remain unchanged: university staff are far more likely to be on the left on the political spectrum. Whether one sees that as a good or bad thing is irrelevant; tenure is an enduring thing.

The funding concerns are real for Harvard, so without the ability to tap into its endowment, the path of least resistance may be the one or some of the 144 billionaires the school counts as alumni.

It is not without irony that the sequel to the “resistance” could star the world’s most privileged institutions and individuals.

Other Matters

If we all were not inured to the burden of ever-increasing costs, graphs like this would get a lot more attention.

What do you do about it?

Control prices? Once again there is a bill to bring rent control back to Massachusetts after a ballot initiative in support failed to materialize for 2024. Chances seem pretty slim, given Boston’s attempt to enact its own form of rent control (“stabilization”) failed to move even past a legislative hearing last year.

Without political consensus (or backing from economic research), a new alternative is quietly emerging: government investing in supply. A new multi-family housing development in Milton has an equity partner in Massachusetts, now with $50M to allocate to make the math work to finance and build new housing across the state. The City of Boston is also working with state, with its own track record as a lead funder in the creation of housing trust in East Boston in 2023.

With high regional costs and unstable macroeconomic conditions, there may be an even greater need for Boston/MA to play the role of intervener in housing production.

The policy question of whether or not District 7 should have a special election to replace Tania Fernandes Anderson quickly became a political one. Arguments about costs, turnout, and inconsistencies all skipped over the more fundamental point that many City Council elections are quite special already.

In 2022, the council seat for East Boston, Charlestown, and parts of downtown was decided by a special election (triggered by, naturally, the special election of the then-Councillor Lydia Edwards to the state senate). Current District 1 Councilor Gabriela Coletta Zapata won her special election in May with 10.2% turnout.

Sounds really low. Until you compare that to District 1’s turnout in the regular November election in 2019.

Larry DiCara and others have chronicled Boston’s “vanishing voters,” leap year, Presidential election voters who are unlikely to vote in state elections and basically never vote in municipal elections. Rather than debating how to better engage or inform these voters, there is a far more simple intervention: hold more elections on the same day.

Research and analysis show not only does ending “off-year” city elections - and pairing them with national and state elections - increase voter turnout (Baltimore turnout jumped 47%!), it positively impacts the share of the Black and Latino vote.

There are counterarguments about costs and election “crowding,” but are those things really more important than more people voting? If we were serious about increasing democratic participation, we would not be talking about the fall of 2025 for a City Council election.

We would be talking about the fall of 2026 or 2028.

https://open.substack.com/pub/johnnogowski/p/hello-death-boston-marathon-1982?r=7pf7u&utm_medium=ios