Boston Focus, 9.12.25

Boston never gets old (except, it is)

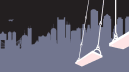

New one-year Census estimates were released this week, reflecting continued shifts in Boston’s demographics.

There has been a bit of post-pandemic bounceback for Boston’s population, up ~25,000 residents and inching back towards 700,000.

That is not true for kids.

You have to be careful with Census data in a town like Boston. Every September 1st we add a ton of new 17 and 18 year college first-years, skewing our counts. Focusing on ages to 0-14 avoids that noise, and earlier grade enrollment is traditionally a very strong predictor of future enrollment.

Boston now has its lowest rate - both in absolute number and percentage of population - of kids since 2010.

From their respective highs, the under 5 population has decreased greater than 17%; kids aged 5-14 are down almost 9%.

The result? Our city is getting older.

The macro drivers - birth rates, housing, affordability, etc. - may be adding another. Both in an interview with Mayor Wu and during this week’s School Committee, the city forecasted enrollment and attendance issues driven by federal immigration policies. The city is already citing lower enrollment (48,128) than 2024-2025, with several weeks until the October 1 enrollment deadline and reports of large numbers of students not reporting.

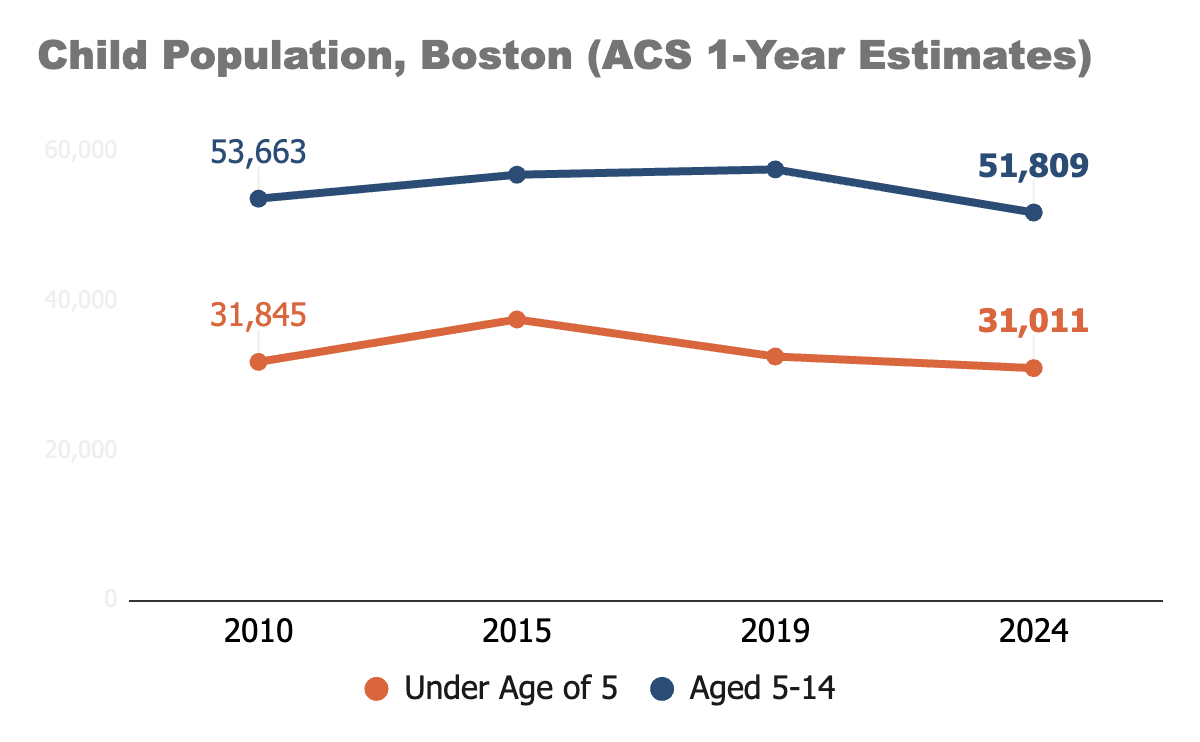

The financial and operational costs of enrollment dips are unique because you pay for them now and later. Even one small cohort digs a hole not just in this year’s budget, but in each that follows until that cohort ages out or bigger ones make up the difference.

That is why, in part, the city had to allocate progressively more funds to cover schools’ enrollment declines (“soft landings”).

It also resurfaces questions about the scope and pace of potential school closings.

More broadly, it is another data point implying the city is in the midst of a bigger shift. With fewer younger children and fewer newcomers as potential new students, Boston may indeed be getting older.

Schools

Boston School Committee met Wednesday. Agenda here. The meeting featured public comment from Mayor Wu and many other comments and data on potential changes to exam school admissions (again). The Committee and the public received verbal updates on enrollment, buses, hiring, etc., but no materials were provided.

The buzz of back-to-school belies the notion that schools are a “vanishing” political issue, particularly at the national level. Locally, the now vanished Boston mayor’s race saw its first and only media assessment of candidates’ education plans just last week. Boston voters did not rank education as a top issue in a recent poll.

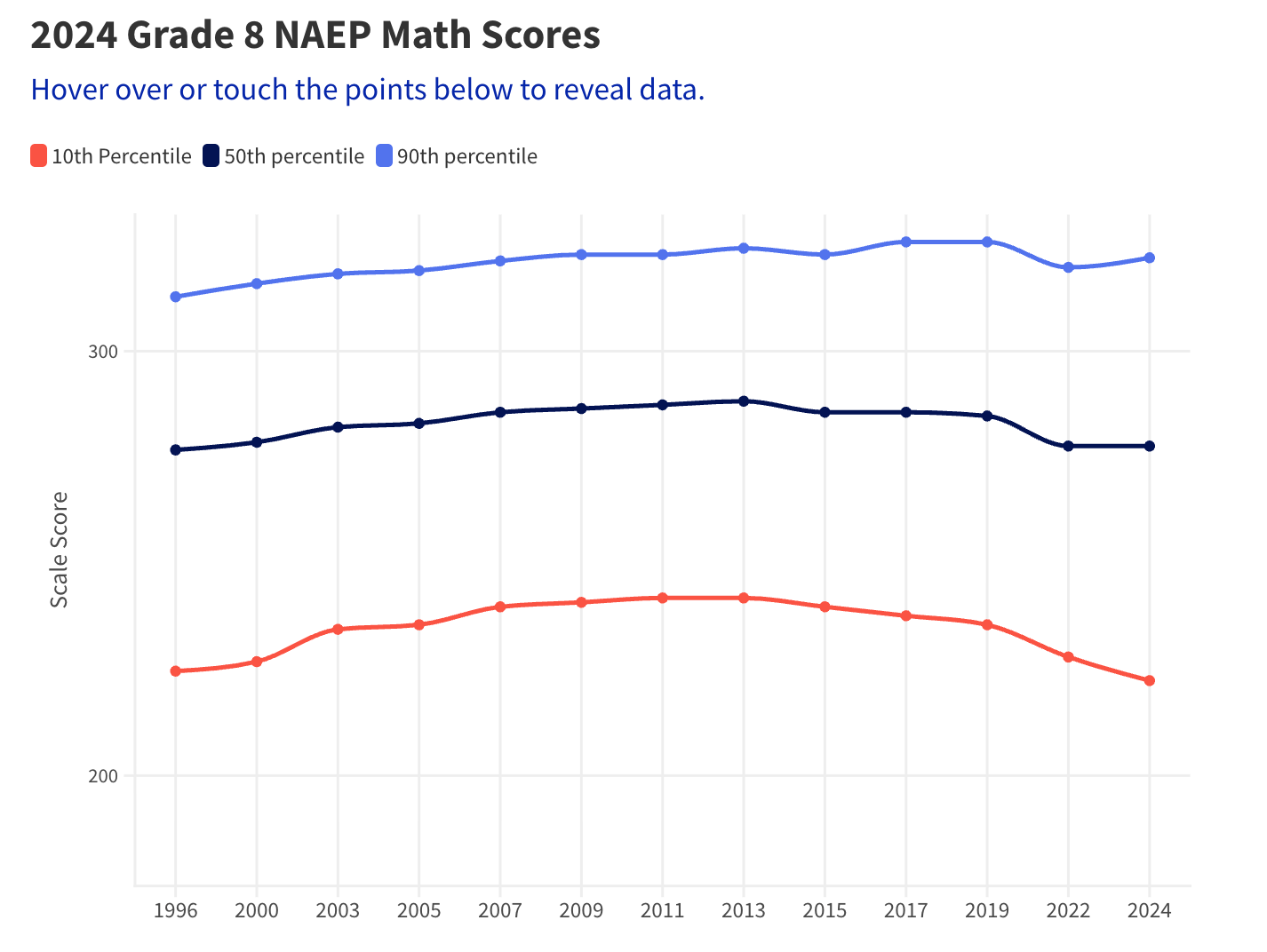

Curious timing. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (the “Nation’s Report Card”) reported student declines again, including some of the lowest reading achievement since 1992.

Eventually 2020 will be too deep in our past to blame this decline on the pandemic. Something else is clearing going on here because “learning loss” started earlier, particularly for our country’s low-income students.

It may be more accurate to describe this phenomenon less as a vanishing and more as a change of appearance. Schools are very much at the center of our politics in the form of culture wars, a phrase we should consider retiring given the violence that happened this week at Utah Valley University. Not an easy time to be going to school: another school shooting in Evergreen High School in Colorado, a stabbing at Madison Park here in Boston, and UMass Boston and nearby schools were in lockdown yesterday afternoon.

Schools are still really important - maybe just not for teaching and learning. The shortcuts probably aren’t helping. OpenAI usage suspiciously coincides with summer break.

So where is there growth? Increasingly, private education. Voucher usage increased 25% last year, and that is before new federal tax incentives to fund vouchers in every state. Even blue Massachusetts is being urged to take a look.

Tufts is the most recent college to become free-ish.

Other Matters

As I landed in Houston in 2017, I was amazed by how much housing there was. It was a sea of gray, concrete and dwellings for miles in every direction.

But this rapid, unregulated growth had a big downside. Later in 2017, rain from Hurricane Harvey flooded the city virtually everywhere.

The tension between housing production and planning/impact is now playing out closer to home. Draft state regulations would significantly reduce required environmental reviews, with the Commonwealth banking on lower costs and faster timelines to shrink the region’s housing shortage.

Sounds good today, but zoning, regulations, and red tape that no one likes can prevent problems later.

What good is abundance if it just ends up being washed away?