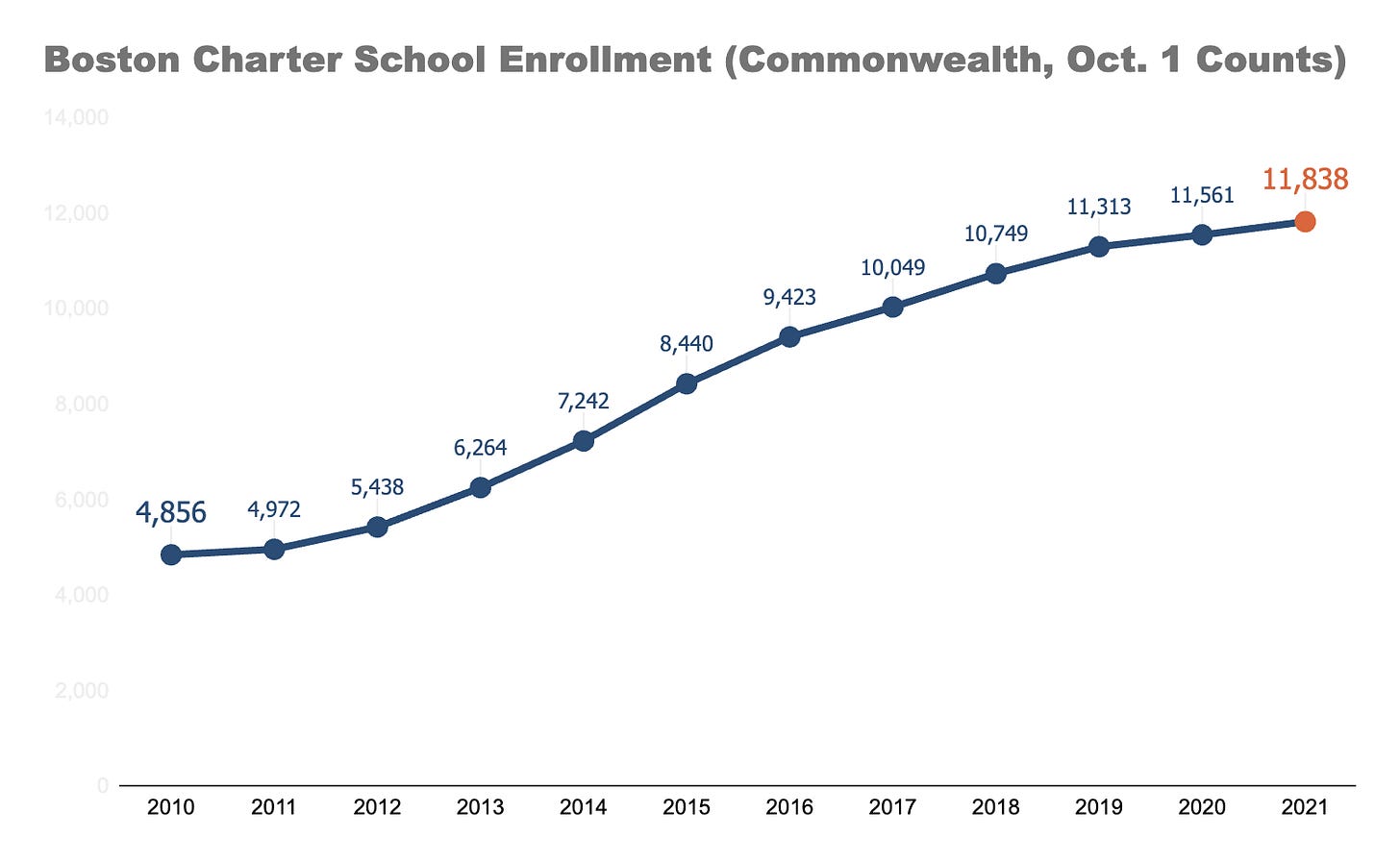

The last generation of schooling in Boston witnessed three significant enrollment shifts:

the decline of Boston’s school-aged population and BPS enrollment;

an increase in the enrollment of English learners (true across MA, too, Tim Daly points out here),

an increase in the enrollment of Boston charter schools

Fifteen years ago, almost to the day, then Governor Deval Patrick signed an Act Relative to the Achievement Gap. After two decades of bipartisan consensus and fueled by the Obama Administration’s Race to the Top initiative, Massachusetts and many other states passed education reform bills, many of which increased access to charter schools.

Boston charter schools were invited to grow. And more Boston families enrolled. A lot more.

Recently released state data indicates that Boston charter schools grew while following practices and policies to promote access to the schools.

Boston charter schools enroll a higher percentage of Black and Latino students than BPS.

Boston charter schools serve nearly the same percentage of high needs students as BPS.

2025 enrollment data indicates that Boston charter schools have begun to mirror BPS in a different way: Boston charter school enrollment has declined by 7% since 2021.

This is partially driven by school closures (Helen Y. Davis last year, and City on a Hill at the end of this year). But the enrollment decline is diffuse; all but three of Boston’s charter schools have lost students.

Of course, there are real policy and political factors that make future Boston charter school enrollment growth virtually impossible. Bipartisan support for charter schools in Massachusetts officially ended on November 8, 2016 with the resounding defeat of the ballot initiative to increase charter school enrollment and the first election of Donald Trump. Opposition to charters - primarily on funding grounds - continues to this day.

In Boston, this point is moot. Boston charter enrollment is capped, and there can be no new allocations of seats because Boston’s is no longer in the bottom 10% of MA districts (a requirement of the 2010 to allow for further charter expansion in a community).

In this context, while facing demographic pressures and/or waning demand, Boston charter school growth is very much a thing of the past.

Schools

Boston School Committee met this week. Full materials here. The big headline coming out of the meeting was a facilities report setting a target of closing ~19 schools by 2030.

What schools? Will new school buildings be built? With what money? For the plans we do know - the five schools slated for closure or merger next year - there was public comment and discussion.

These recommendations rely on this enrollment analysis.

Why wouldn’t kindergarten projections be tied to birth rates (which has declined) or the age 0-5 population (which has declined)? This is the kind of thing that independent experts suss out in long-term facilities planning, like what Somerville did recently, for example.

Boston’s weekly City Council meeting was dominated by another BPS building project. With demolition readying for White Stadium and a potentially higher tag, it may be on the City Council agenda again next week.

Boston has received federal funds to further expand its electric bus fleet.

10 separate bills were filed in the Massachusetts legislature to limit cell phone use in schools, but Attorney General Andrea Campbell’s bill is drawing the most attention, already garnering support from the Secretary of Education and the Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA). Those who follow my writing for the Boston Globe know where I stand on this.

In addition to the right to strike, the MTA is also seeking legislation to set minimum educator salaries; the average MA teacher salary - last reported in 2021 - is $86,118.

The Governor followed through on her remarks from the State of the Commonwealth and convened a council to create new uniform high school graduation standards. The Governor’s proposed FY26 budget featured pretty significant education investments: +$400M more for local aid for schools, universal free meals, literacy curriculum and tutors, early childhood grants, and capital improvements for the state higher education facilities.

Updated National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) data always yields interesting findings. First, less students and more staff is a national PK-12 trend.

And Black and Latino students continue to have less access to certified teachers and STEM courses while being disciplined at higher rates.

The new US Deputy Secretary of Education was a finalist for Massachusetts Commissioner in 2018.

Other Matters

But appointments are not exactly the talk of federal policy right now. President Trump’s directives on immigration are opening the schoolhouse doors for investigations and deportations. Expect real ripple effects for attendance and enrollment. Community disruption seems imminent. The national quickly has become local, as mayors and superintendent decide if to comply (Worcester isn’t).

But is it fair to frame this as a national/local binary? Last April, immigration was found to be the number one issue amongst Massachusetts voters. The prospect of the state adjusting shelter laws set off a week of media coverage and intense political rhetoric.

As David Leonhardt of the New York Times surmised, regardless of your personal positions on immigration, the American public displays elements of narrow consensus, nuance, and intense disagreement on the issue.

In other words, an open front for a culture war. The purpose is not to “win,” but to continuously fight, creating sides and inviting clicks that accrue benefits for the cultural warriors themselves, big costs for targeted individuals or groups, and less direct benefits and costs for the broader public.

Immigration, the elimination of DEI programs at colleges and universities, and who plays on what youth sports teams fit this paradigm, which is precisely why you will keep reading about them.

Culture wars don’t end with treaties of sensible, lasting public policy.