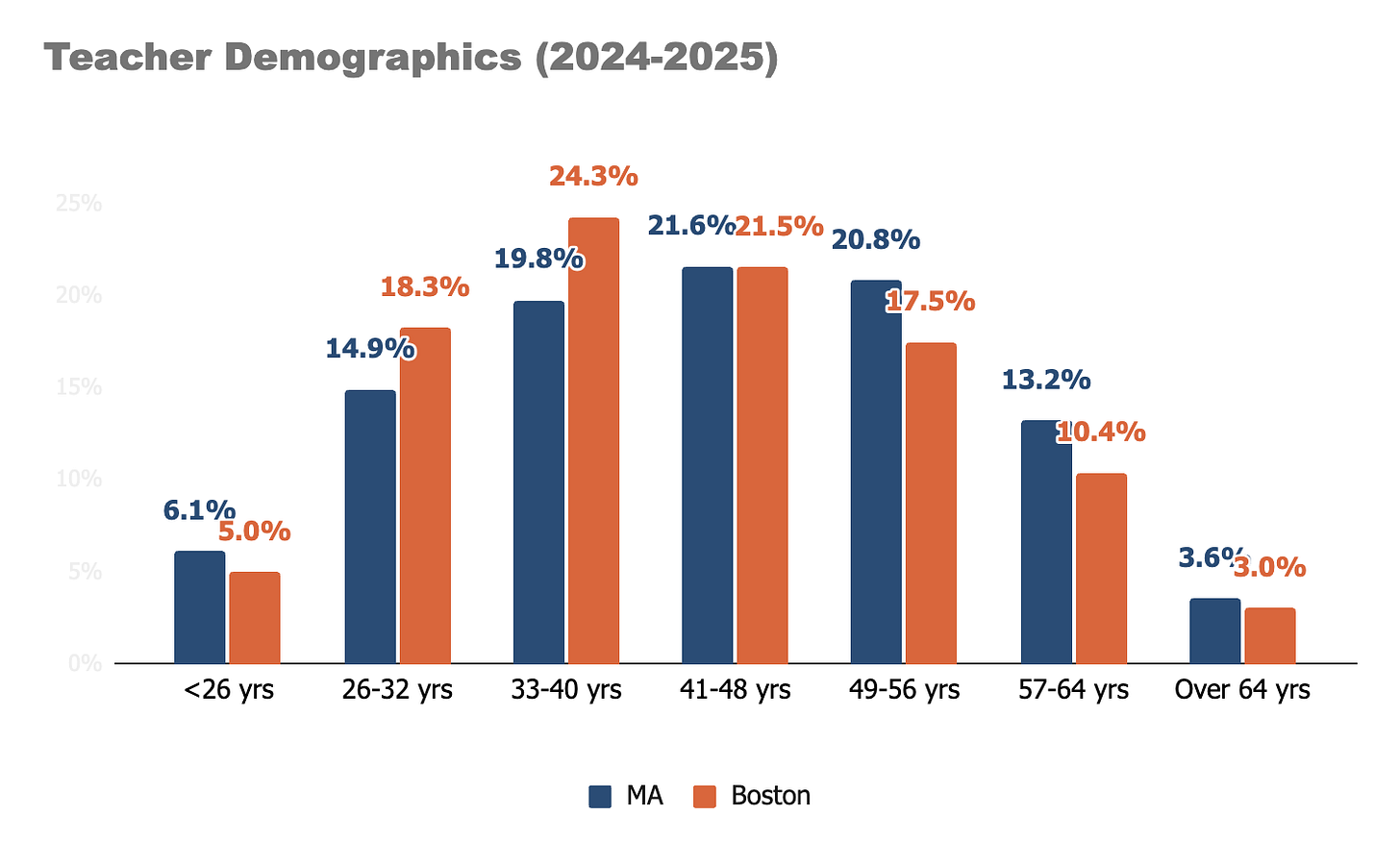

Released state data reveals how similar (or not) Boston teachers are to their peers around the Commonwealth.

First off, Boston’s teachers are slightly younger, with nearly half younger than 40.

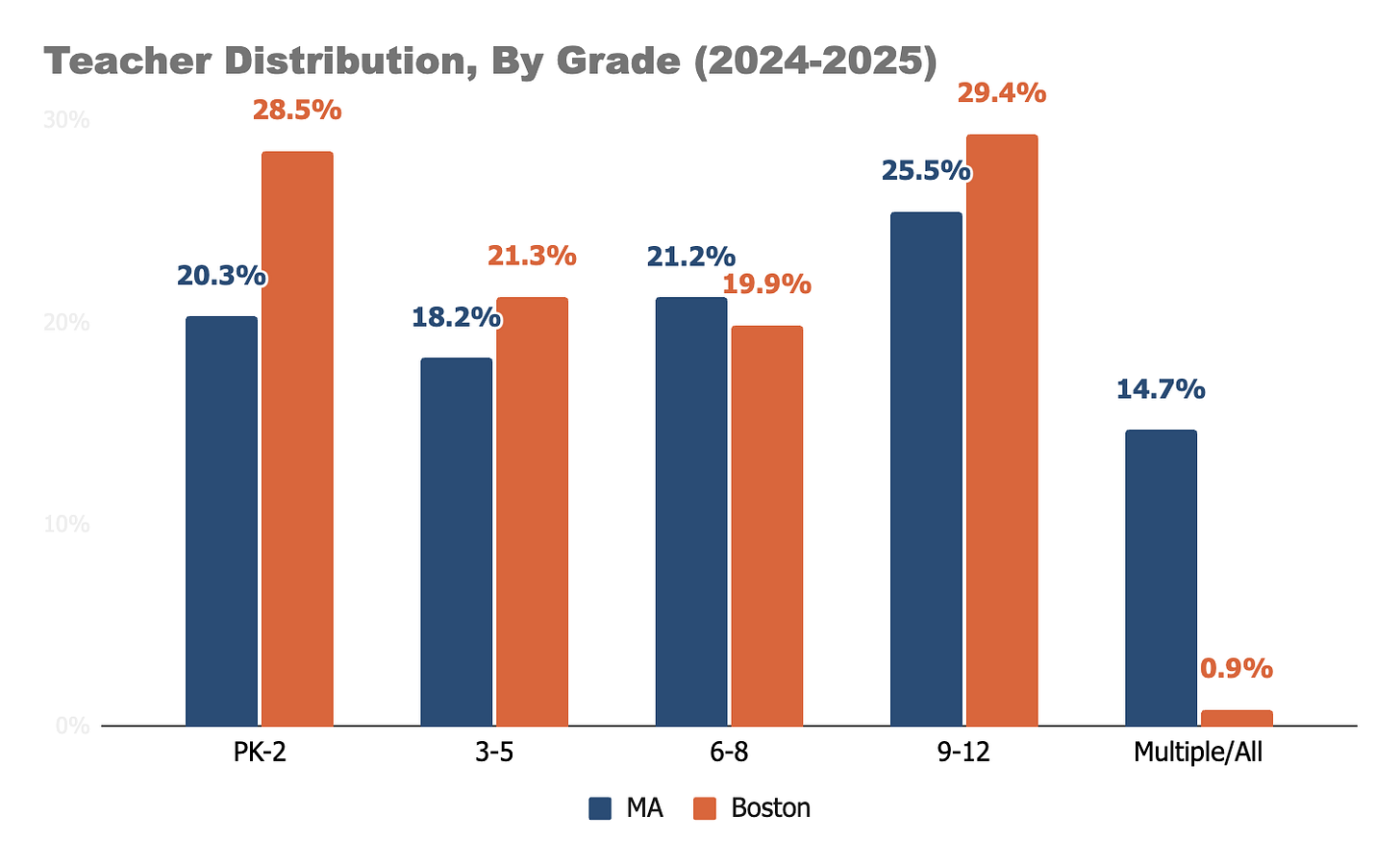

Boston’s teachers are deployed differently than most parts of Massachusetts. Nearly one out of seven Massachusetts teachers instruct across gradespans, but that is very rare in Boston schools.

Lower enrollment and the elimination of middle school programs drive the lower ratio for grades 6-8, with significantly higher allocations to the youngest (PK-2) and oldest (9-12) students.

Teacher assignments generally track with student enrollment.

That is less so the case with student demography. Firstly, Boston teachers’ racial composition varies greatly from Massachusetts averages.

6 out of 7 Massachusetts public school teachers identify as white; about 1 out 2 do in Boston. 1 out 3 of all Massachusetts Black public school teachers work in Boston. This is by design, after all Boston has explicit targets for hiring by race that track back to the decisions of Judge Garrity in 1974.

It is worth noting that Garrity may have set different targets today. Although it is possible that the majority of Boston’s students could be Latino within a few years, only ~15% of teachers identify as Latino.

The biggest divide, however, is by gender.1

The pandemic raised questions about the ability to retain teachers and attract new ones but, in Boston and Massachusetts, the early data indicated minimal impact.

Public education is now experiencing a new, two-sided disruption. On one side, uncertainty about funding; in a field where greater than 80% of budgets go to staffing, funding means your job, or a colleague’s. On the other side, there is certainty about what the current federal administration wants taught and who gets hired.

Attracting and retaining public school teachers - particularly a diverse pool - was already facing strong enough social and market headwinds.

It may prove to be getting more difficult.

Perhaps that is the intended result.

Schools

A federal judge is allowing White Stadium demolition and construction to continue. Demolition is nearly half done, with the projected cost doubled from the current capital budget.

Worry and threats met reality when the Trump Administration abruptly cancelled the remaining pandemic funds for schools. That means $106M in funding lost for Massachusetts schools, with Springfield accounting for nearly half of that amount. Unlike the highly targeted nature of much of the federal education agenda, this action applied to 41 states and even private schools, many of whom simply used waivers to complete capital projects.

This is bound to only create more tension - and political opportunity - in an already tense budget season. More student walkouts this week, a Way and Means hearing gave the Healey Administration the angry constituent meeting many members of Congress are trying to avoid, and the Massachusetts Teachers Association is already positioning for state revenue.

Even with more consensus and several bills to ban cell phone usage in Massachusetts schools, there is nuance. Small sample size, but research out of the UK implies that increased cell phone usage by students, making up for lost screen time in school, may erase gains from the intervention. Another Massachusetts bill seeks to limit social media’s algorithmic targeting of young people. And, of course, schools need to be giving students good reasons to look up from their screens to begin with.

The bifurcation of the higher education market in two acts: some Boston area colleges pass the $100,000 price tag while others are reported in financial danger. Harvard is the most recent university to find itself in financial danger with a list of federal demands.

Other Matters

Massachusetts sponsors of a bill to limit online gambling evoked the early stages of the opioid crisis.

With housing so limited and expensive, the Allston land unlocked by moving the Mass Pike would seem to naturally follow the path of Suffolk Downs or Dorchester Bay City. But the state’s interest in using that land to support and expand transit service reveals an interesting trade-off. What produces more benefits: more housing within Boston or better access to Boston (which could spur more, probably less expensive housing in the metro Boston area)?

Massachusetts reports non-binary students, not teachers.